How to Grow Tomatoes

Tomatoes were likely first bred from wild nightshade plants with tiny fruit about 7,000 years ago in Mesoamerica. The original wild fruits descended from a Peruvian and Ecuadorian plant that is similar to modern cherry tomatoes.

Although tomatoes had been eaten by people in the Americas for thousands of years when they were first introduced to the rest of the world, many cultures were wary of the new fruits, and some people considered them toxic. They eventually came around, and nowadays, tomatoes are considered critical elements of cuisines far from their homeland in Italy, The Middle East, and India.

While they’re primarily regarded for their delicious flavor, tomatoes contain a host of vitamins and antioxidants, so they’re also a great addition to a balanced homegrown diet. In our house, we eat a ton of fresh tomatoes during the summer and also can, sun-dry, and freeze enough tomatoes to eat them all winter.

Determinate versus Indeterminate Tomatoes

At a high level, there are two types of tomato plants: determinate and indeterminate. Determinate tomato plants like Romas grow to a certain height and then produce all of their fruit at once. This is ideal if you plan to use your tomatoes for sauce or some other processing project where you want a big pile all at once.

On the other hand, if you want a consistent supply of tomatoes throughout the growing season, you should focus on indeterminate varieties like Cherokee Purple, which continue to grow and produce fruit until they succumb to disease or the winter. We grow a mix of the two so we can eat fresh tomatoes from our indeterminate varieties all summer and then harvest a big pile from our determinate tomatoes tomake sauce.

Tomato Growing Conditions

If you are growing your tomatoes from seed, start your seeds in pots or trays indoors about a month before your average last frost date. If you find your seedlings are getting leggy—meaning the stem is growing lanky and tall with relatively few leaves—you can transfer it to a larger pot and bury the stem, which will generate more roots.

After your average last frost date has passed and your plants are at least six inches tall, you can harden them off and transfer them into your garden beds. We like to clip the leaves off of the lower two-thirds of the stem and bury the plant so that only the top third is above the soil. The stem of your tomato plant will produce roots wherever it is buried, so planting them deeply will help your plants develop a robust root system.

Tomatoes are susceptible to many soil-borne fungal diseases commonly transferred to the plant from soil splashing onto the leaves during rain storms or irrigation. A great trick to reduce their risk of contracting fungal disease is to cover the soil beneath your tomatoes with a thick layer of straw or leaf mulch. This will also help retain moisture in the soil and suppress weeds. Additionally, we clip off any tomato leaves that grow long enough to touch the ground as the plant matures.

How to Trellis Tomato Plants

Although we think of tomatoes as upright plants, they naturally grow as a ground-dwelling vine and need to be supported by a trellis or stake to grow upright. Our preferred method of trellising tomatoes is the Florida Weave.

The Florida Weave entails placing two steaks on either end of your row of tomatoes and wrapping some twine around the stakes to prop up the tomato plants. Start with one layer of twine, and then every couple weeks when the plants start to topple over, add another layer of twine six inches to a foot above the last. Other growers use single stakes for each tomato plant which they individually tie to the stake. As long as the tomato plant is held up above the ground and able to receive sunlight and water, the world is your oyster.

How to Sucker Tomato Plants

Because tomatoes are so susceptible to fungal disease, keeping their canopy of leaves thinned out to allow airflow is very important. One of the best methods to keep them from getting too crowded is to “sucker” them.

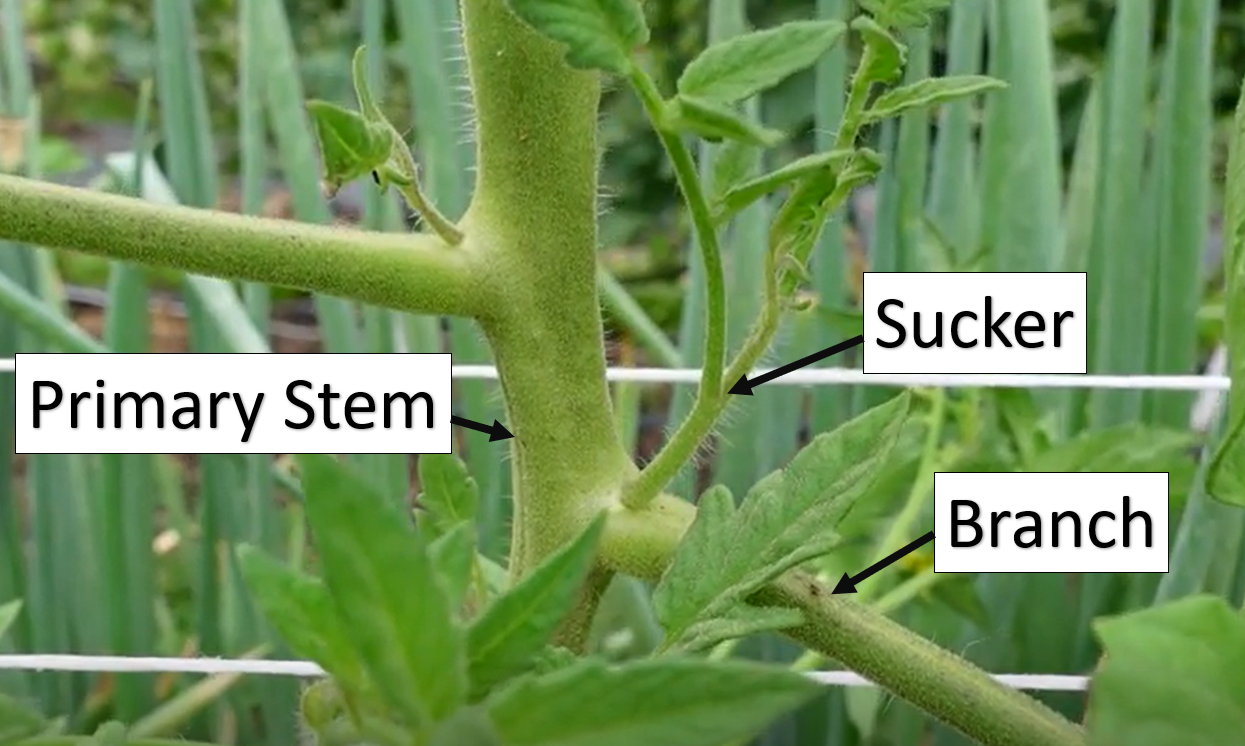

Suckering is a very simple process once you know what you’re looking at. Each tomato plant has a primary stem, and along the stem, there are branches, leaves, and “suckers.” The branches and leaves grow at a 90-degree angle to the main stem, and the sucker usually grows out of the “armpit” of this junction at a 45-degree angle. You can either snap them off when they’re small and tender or cut them out if you find them when they’re a little bigger.

Tomato Pests and Diseases

Tomato hornworms are the scourge of many tomato growers in North America. These pinky-sized caterpillars can defoliate an entire tomato plant in a number of days. Lucky for us, there is a parasitic wasp that uses tomato hornworms as one of its primary hosts. As long as your garden has a healthy population of native insects, you’ll often find tomato hornworms with white cocoons hanging off of their back, which essentially means they’re a zombie and no longer a threat to your plants. If you find hornworms without the parasites, you can simply pull them off the plant and smash them or—better yet—feed them to some chickens if you have them. If your tomatoes are truly infested, and hand-picking is not a viable option, the organic pesticidebacillus thuringiensis(BT) is effective against them.

As I mentioned earlier, tomatoes are very susceptible to fungal disease. The best way to mitigate this is to keep their leaves thinned out and plant them in an area with good air flow and plenty of sunshine. Your tomatoes will most likely succumb to a fungal disease like late blight before the winter hits, but this is totally normal, and as long as you’ve already harvested a good pile of tomatoes, you shouldn’t worry too much about it. Remember to remove all of your spent tomato plants from the garden and compost or burn them to prevent the fungal disease from spreading prematurely the following season.

Tomato Harvest and Use

As soon as your tomatoes begin to blush from green to their mature color, a chemical reaction begins in the fruit and they’ll continue to ripen even after they are picked. You can let your tomatoes ripen fully on the vine, but if your garden is receiving a lot of rainfall, your ripe tomatoes run the risk of splitting and rotting on the vine. If there is heavy rain in the forecast we usually harvest any of our tomatoes that are blushing and set them on our kitchen counter to finish ripening.

There’s nothing quite like a fresh homegrown tomato sliced and thrown on a sandwich or salad, but eventually, I think you’ll find that you havemore tomatoes than you know what to do with. If this is the case, you can either can your tomatoes whole, dehydrate them for sun-dried tomatoes or freeze them in freezer bags to use for sauce later in the year. If you plan to can your tomatoes, make sure to follow atried and true canning recipeto avoid the risk of spoilage or botulism.

Want to learn more about growing and cooking with tomatoes? Check out these videos:How to Prune and Stake TomatoesandHow to Make Tomato Sauce. And these articles:What to Do With an Abundance of Tomatoesand thisBurger with Tomato Jam Recipe.

Shop

Sign In or Create a Free Account

Related

Gardening

How to Grow Potatoes

Cooking Techniques

What to Do With an Abundance of Tomatoes