The greased line fishing technique was a 1903 revelation by the late Arthur Wood of Scotland. It occurred to him one day while observing the behaviour of salmon and their disinterest to the deeply sunk fly.

Across the world, anglers actively used water-absorbing lines and heavily gauged hooks with the desire to fish their flies deep in the water column.

Mr. Wood soon perfected and popularized a revolutionary change. He learned that if he could coat the material of the line in a substance that would stay afloat, he could then swing his fly in a subsurface and somewhat drag-free presentation.

At the time, the best flotation materials were variations of grease; mucilin, lanolin, and animal fat were all thought to be suitable.

As I personally own and fish a silk line on my single-hand rod, it is in my experience that silk lines cast as seamlessly and effortless as the fly lines of today.

But maintenance can take its toll on the most patient of anglers. I know that for me, having to remove the line from the reel, dry it out overnight, restring it in the morning, grease it, apply felt, cotton, paper towel, stay busy until it dries, fish for four hours, and then have to do it all again… basically ensures only occasional use.

Traditionally fly lines were made from hair, but as time went on line makers progressed to the addition of silk to increase the strength of the lines and to tone down excessive roughness. Three threads were loosely twisted together and each strand was then braided to form a fly line. Prior to this, line had only been twisted but it found itself liable to kink. The braid helped to prevent this problem.

Soon it was silk that dominated the market. It was superior to hair, ordinary linen lines, lines mixed with jute, or lines comprised of scrap silk from dresses and stockings.

Two types of silk were used: raw and boiled. Raw silk was that which had been spun by the worm, with the gum slowly discharging to hold the filaments together (much like a cocoon). Boiled silk, on the other hand, eliminated this gum thus losing around 30% of its weight and requiring additional material which in turn made it stronger.

So Mr. Wood, innovative and experimental, coated these same lines with floating substance and, while always watching his line, maintained control of it to ensure a natural looking swing. When done right, the fly was presented to the fish broadside, its position managed through delicate control.

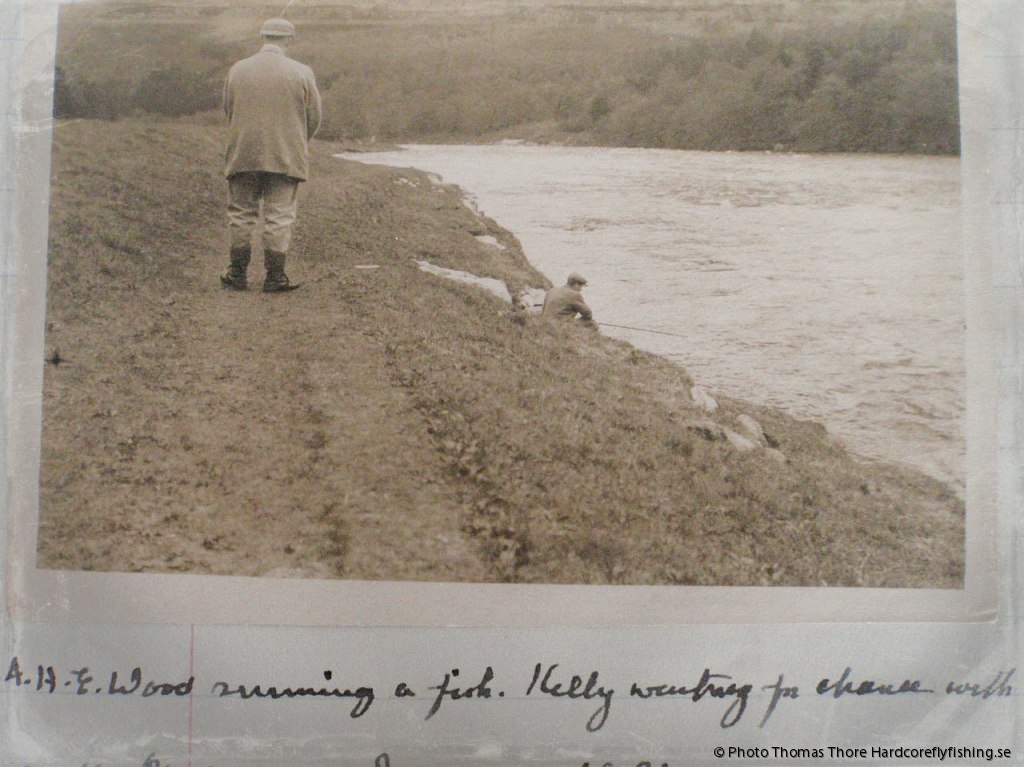

Wood was most recognized for the time he spent using this semi-natural presentation on his Cairnton beat on the River Dee. By using the water’s current, hydraulics and speed, he played the eddies and used flies shockingly sparse in attempts to imitate fish or other small creatures in distress. He has been credited for “inventing the mend” and his skill in line manipulation was unparalleled.

He preferred a small belly of downstream line to form just several feet in the leader, where it would pull slightly to assist the fly in hooking the fish.

I specifically chose to feature this methodology in hopes that I might enlighten others not only to participate in its success, but also to learn more about its efficiency.

Truthfully, I first learned of the greased line technique when I was a teenager looking to learn all I could on the sport. I had been told that to “grease line fish” was to fish a wet fly on a dry line, but there had been no more elaboration.

Years of guiding and conversing with other fishermen showed me that I was not alone in my confusion. In fact, there seemed to be a clear line between those anglers who were familiar with the intricacies of the greased line practise and those who weren’t – a line that teetered uncertainly on what I can only sum up to being age.

Diving into books, written explanations, diagrams and charts, I began to unfold the true definition of the grease line method and hoped to blur what seemed to be such a crisp gap between generations.

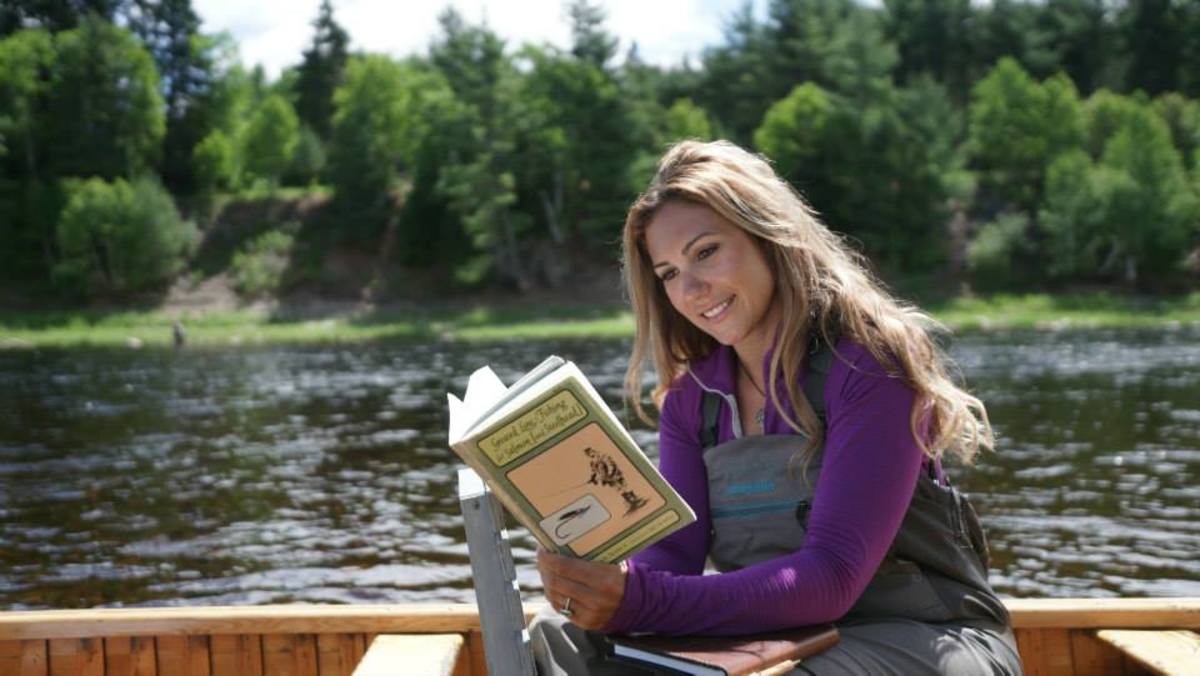

It was inevitable that I would eventually purchase the book that started it all…

The idea of the original greased line fishing book was conceived in 1933 when the elderly A.H.E. Wood discussed his concepts with writer and angler, Jock Scott. Aging and armed with years of grease lining notes, diaries and records based upon his own trials and errors, Mr. Wood allowed Jock Scott to take the reins on a book that would impact the history of fly-fishing “how-to’s” for centuries to come.

The book was a success in its day, and long after Mr. Wood had perished, the pages of Greased Line Fishing for Salmon lived on in the lives of Atlantic salmon anglers. What Mr. Wood likely didn’t expect was that this book would reach the west-coast of North America where an abundance of knowledge-hungry steelhead fishermen were looking to enhance their skills.

That particular era of angler was accustomed to finding their way around the pages of peers and elders, and their desire to learn sparked a reprint and revision in the 1980’s when the book was introduced by Bill McMillan, appropriately titled, Greased Line Fishing for Salmon (and Steelhead).

But as equipment changed, books became less popular and immediate results became the expected norm. The greased line practise gradually lost much of its following and a simplistic approach was adopted: sink it, cast it, swing it, step down, repeat.

So this year I brought some of the knowledge I’d learned with me up to British Columbia’s steelhead mecca, and tried to make Mr. Wood proud. When I would manage a fish, I’d release it in silence and take a moment to connect with this man I had never met.

That connection made the effort all the more worthwhile and soon it was less the fish I sought, and more so an invisible force that bonded me with the ghosts who were silently leading me to my catch.

My floating line drew scepticism in runs (particular those with depth) but I stayed persistent with my presentation. There was an occasional fish caught behind me by friends with heavy tips and large flies, but the differences in numbers was neither abundant nor important. What was significant however, was the interest the method piqued by those who had never witnessed such an approach.

Scepticism isn’t new when it comes this topic. Wood’s grease lining book was at times said to be biased, as he rarely left his beat on the river Dee in Scotland; a river well suited to the technique he developed. Long stretches of flat gradient provide a relatively consistent current, whereas the rivers of the west coast are often comparatively steeper, resulting in a more dramatic change in water flows.

Wood and cane rods up to fifteen feet long were used, but overhead casts ensured the stoic water wasn’t disrupted. Double hand rods originated in the UK, but it wasn’t until years later that most of the casts we now know as ‘Spey casts’ were developed.

Fear of water disruption was a genuine concern at that time. Within my own reading lists, I have read reports by the likes of Frederick Hill, Richard Waddington and Arthur Wood who had all expressed certainty that fish held either in the surface of the water column, or amidst the rocky bottom of the river floor. Whether it be true or otherwise, belief that fish did not sit mid-column was enough of a caution to use care when frolicking about on the water’s surface.

The technique was best-suited to low water conditions where the fly could provoke enough action from the fish to allow the angler to see the disturbance, and in turn be able to drop line into the water for a thorough hook set.

While I am years away from perfecting the technique, I began to choose traditional patterns, cast cross-stream (or slightly up or down), and then manipulate my floating line in such a way that the fly was suspended just below or subsurface on a slow swing.

The goal is to bring the fly down and cross stream so as to avoid any of the drag that speeds the fly in an unnatural manner to the current.

As the fly is presented broadside, it allows the fish to see it better. Wood argued that in addition to this, the materials were able to move with more motion and that the hook had less resistance in the event that a fish put its mouth around it.

He quotes:

“There are, of course, all sorts of eddies and places where the fish lie, and all have to be fished differently, so as to present the fly to the fish at the angle at which it is best able to see, most likely to be tempted and not come short.

Avoid any unnatural drag at all costs. As there is little a fish does not see, the fly ought to behave naturally all the time, as an insect or other live creature would do in the water, and try to let the fly move with all the eddies it meets as will any living thing that is trying to move in the water with the stream and across.

If you swim across a river, you have to swim at an angle to the stream and make use of all the eddies; but if you have a thick rope tied to your waist which someone on shore was holding, you would soon be in trouble. The current would get hold of the rope and belly it downstream, then you’d have to struggle hard and face more upstream, and in the end get pulled down backwards. No living creature behaves in that way, and the fish will wonder what a dragging fly is, and, even if they go for it, it will probably be dragged out of their mouths — “fish coming short,” so called!”

He did not believe in short strikes and was firm in his stance that it was only by the fault of said angler when this would occur.

By using the rod tip as his main hook-setting tool, he rarely set the hook on fish, quite certain that he could get a better set if the current and fish did the work instead.

Rather than striking, he would hold his rod low in slow water and higher in faster water, to allow a small downstream belly several feet in front of the fly to catch the current and adhere to the fish’s mouth with natural pull.

In the ever difficult situation where the fly was taken on the hang-down (the ‘dangle’ in the Spey world), he would hold his rod tip high and then drop it low into the water to allow any available line to be aided downstream by the current, and hopefully, into the fish’s maxillary.

Chapters on gear and water conditions expose themselves on the yellowing pages of my copy of Greased Line Fishing for Salmon, and diagrams help to piece it all together.

Photos of the large man clad in his dressy attire ignite a spark of curiosity in my mind. What was he like? What would he choose to fish today? Would he have changed his ways?

Page upon page glows with an admiration for his beloved greased line technique. His words so full of vigour and enthusiasm that they speed my fingers to lace my boots.

Is this a way of fishing that is slowly being forgotten?

Is it because it catches less of the fish today?

Or is it because it’s catching less of the fishermen from tomorrow?

There’s only one way to find out and it costs a library card, 226 pages, a day of reading time and a season of experimenting.

I promise that it is worth every single second.

Conversation