Wild Ramps: The Complete Guide to Finding and Eating Wild Leeks

Spring is a glorious time of year. Nature wakes from its winter slumber, turkey season kicks off, open water fishing gets into full swing, and best of all,foraging opportunitiesbegin to sprout at every turn. Right now, we are smack dab in the middle of the season for ramps, also known as wild leeks. Similar in smell to onions, ramps represent one of the first signs that warmer weather has arrived to stay. As an early spring ephemeral, they conclude the majority of their growth before the leaves of canopy trees have formed and shaded out the forest floor. They’re usually gone or inedible by early summer.

Identifying Wild Ramps

Ramps belong to the genusAllium, which also includes domestic onion, garlic, shallot, leek, and other wild onion species. The ramp’s regional range extends from northern Minnesota, east through southern Canada to Nova Scotia, and as far south as Missouri and Appalachia. Ramp leaves are bright green and grow up to a foot in length by about 3 inches wide. Generally, each plant has two leaves that are anchored below ground by a white bulb similar to that of green onion. The stem is also a great indicator. Look for a red hue that runs from the base of the leaf to the bulb.

Where Do Ramps Grow

The best and only time of year to locate this beauty is from the first warm days to the end of spring. By the beginning of summer, ramps will be flowering and the leaves all but withered away as they prepare to regenerate for the coming year. Or, the leaves will be chewed up by critters and insects who also know the great flavor.

Start by searching your local fishing streams and hunting grounds. It’s always good to have a second option if the first goes awry. Woodlands with partial shade, streambanks, riparian zones, and ravines are great locations for narrowing your search. Hardwood forests with rich, moist, well-drained soil are reliable and maple stands always seem to be a gold mine for me. I’ve also found that where trout lilies emerge, ramps are not far away.

Proper Harvesting Practices for Wild Ramps

The popularity of ramps has grown exponentially over the past 10 years as restaurants and markets alike began to tout this unique plant. But many foraging experts say the growth in demand has contributed to over-harvest. As popularity continues to grow, managing these practices will become even harder. Top-dollar payouts for foraged items like ramps can be very tempting, but visiting a patch only occasionally and harvesting properly will ensure that the patch thrives into the future. The same goes for any wild plant or mushroom.

Ramps take a very long time to complete a growth cycle from seed to flower—anywhere from three to 10 years, depending on the soil, habitat, and climate for a single plant to reach seeding maturity. It takes even longer for a thick colony to form. If a patch is over-harvested, it may take over 20 years for it to recover. Sound harvesting technique is key to knowing that when you return to your patch the sweet aroma of ramps will still be there to greet you.

Take only a few leaves from each plant cluster or a leaf from a single plant here and there. Spread your harvesting evenly throughout the patch. Don’t remove the entire plant. If you would like some bulbs for personal use, only take what you need. Uprooting the whole plant at every turn is what will kill your patch. Another popular method is using a knife to cut the bulb just above the root structure. Always assume that you are not the only person that found that patch. Someone else will likely come along and discover it too.

You can also consider cultivating a ramp patch of your own. Ramps transfer very well and will replant easily to populate your land. Simply remove a handful with the entire root structure intact and bring them home. Be patient, but you may eventually not have to go out looking at all.

I’ve honed in on a handful of ways that I enjoy using ramps. I like to focus on ways to process and store them in a manner that allows me to enjoy their unique flavor the entire year. Most of my methods require only the leaves and stems. As much as I enjoy the bulbs, I tend only to take enough for a jar or two of pickles. The upside to this is my forays tend to be quick and clean. Snip a couple of leaves here, a couple there, and before you know it, you’re ready to head home and have some fun.

Butter, above all else, is the first thing that I make with ramps. I make 4 or 5 pounds of the stuff every spring. It’s tricky to get the right consistency, so you need the right equipment and technique. I’ve found that standard blenders just don’t have the firepower to get the job done, so a quality machine is mandatory. I prefer thebullet-style jarsover a big blender jug like you’d use for margaritas.

Once mixed and cooled, I wrap individual portions of butter in plastic wrap similar to store-bought sticks and vacuum seal them. They freeze great and hold their flavor through the seasons.

Blanched and Frozen Wild Ramps

I always put a fair amount of ramps away into the freezer for future use. Simply blanch the leaves for a few seconds in boiling, salted water then shock them in an ice bath to halt the leaves from cooking. This method maintains the ramp’s vibrant color and fantastic flavor. I like to vacuum seal the blanched leaves in small portions for later use. Pureed, the blanched ramp leaves work great in doughs, mashed potatoes, cornbread, soup, pesto, and more. Frankly, the sky’s the limit here.

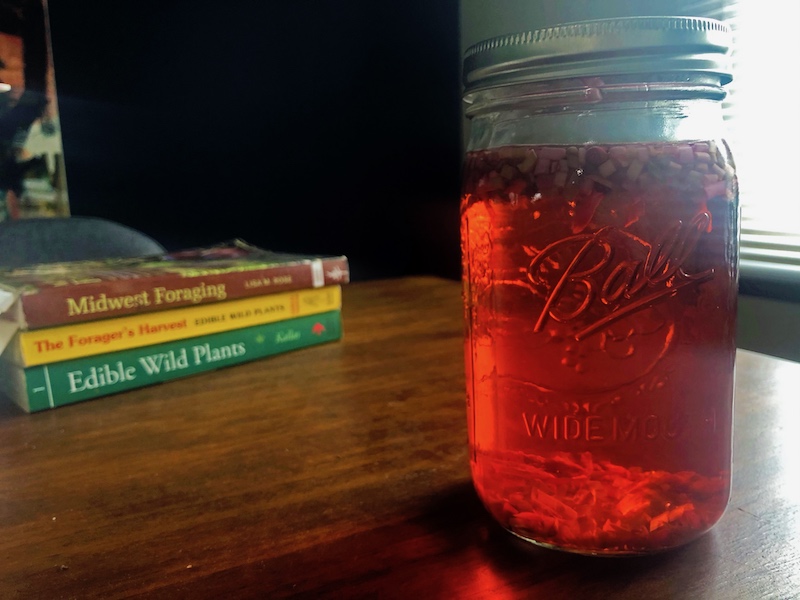

Vinegar and Pickles

If I’ve had a successful day picking ramps, I always stop and grab jugs of white and apple cider vinegar on the way home—critical components to great pickles but also a great vessel for flavoring. I like to fill a couple of quart jars with the vinegar and add chopped ramp stems and leaves. The ramps effectively add their distinct flavor and color the vinegar a bright pink. I use this colored vinegar for everything, including my pickles. If you did happen to harvest some bulbs, they are fantastic as pickles by themselves. Use with your favorite pickling recipe and store for future use.

Wild Ramp Onion Powder

I just started playing with this method in the last couple of years. The stems and bottom of the ramp leaves are perfect for it. I cut them down to roughly 2 inches in length and dry them in the dehydrator. It takes 24 to 36 hours, but the result is well worth it. After they’ve cooled out of the dehydrator, I buzz them to a powder in my trusty NutriBullet. The result is a substitute for onion powder that’s out of this world.

Wild Ramp Hot Sauce

Need I say more? Blanched ramp leaves are the perfect base for a basic hot sauce recipe. One of my personal favorites recipes is to jam a bunch of cleaned leaves into a Mason jar with some salt and let them ferment for a couple of weeks. It stinks to high hell, but the result is the best hot sauce base money can’t buy.

Of course, don’t forget to eat some fresh. Add chopped ramp leaves to pasta, salad, or eggs. You can substitute ramps for onions and garlic in any recipe. Experiment and have fun. Far too often we worry about how to preserve wild edibles for later use when sometimes it’s just best to enjoy them right away. So, when you’re heading to your favorite trout stream or turkey hunting haunt this spring, make sure to keep your eyes peeled and nostrils flared. You might just come home with some wild leeks to pair with the day’s kill. Happy harvesting.

Shop

Sign In or Create a Free Account

Related

Foraging

How to Sustainably Harvest Ramps

Gardening

How to Grow Ramps