Six minutes had elapsed and the pickerel never flinched. It’s body was angled slightly downward, and aside from the most delicate flutter of its pectoral fins, it was statuesque. Just a few inches in front of its face, my shiner swam in tight circles. It wasn’t frantic. The bait just maintained a slow-paced tail beat. Around and around and around it went. The pickerel just watched.

I was seeing all of this on the screen of an underwater camera. That shiner was doing donuts on the terminal end of a tip-up line. By the time this soap opera started, my buddies and I had already put a few good pickerel on the ice, so it wasn’t exactly a slow morning or finicky bite. Why then was the pickerel I was watching so reluctant to kill that shiner? I certainly understood that the camera hanging down there can get any fish’s hackles up; none of the other tip-ups had electronics dangling next to their baits. But the pickerel’s eyes were locked on the shiner, not the camera. It knew damn well that it was a quality meal, but six minutes turned into 10 and the staredown continued.

Twelve minutes in, the shiner ran out of steam. It broke its rhythmic cadence and stopped swimming as if to catch its breath. I was glued to the screen as hard as I was the first time I saw that glass of water ripple in Jurassic Park. The stone pickerel suddenly came to life and tilted down a little more. The second that shiner kicked its tail again it was pulverized.

The immediate lesson I learned was one cannot assume every tip-up flag that flies is the result of instant commitment from a fish. That far flag that finally went off after an hour might’ve had a fish looking at the bait for 30 minutes. But that 12 minutes of observation actually taught me more about what to do right after ice-off.

Held In Suspense I’m a sucker for chain pickerel. In fact, I’ve made it somewhat of a personal mission to sing their praises loudly in written and video form over the years. They are available to more people than pike and muskies, and while they may not grow as big, they are voracious and put a good bend in a light rod. They’re also at their heaviest right after ice-off, fat with eggs as they prepare to spawn. Where I live in the Northeast, that’s late February and early March, and if we had good ice at all (which is very hit or miss in my area), it’s usually gone by March 1. It’s that time of year a lot of folks call “mud season,” but while the air is getting warmer, the water hasn’t caught up.

Prior to the 12-minute countdown to death I witnessed on the ice, my late winter/early spring pickerel program relied on suspending jerkbaits, and I was plenty successful. But “suspending” is a loaded word in the fishing world.

Many lure makers tout their baits as suspending. Talk to a die-hard bass guy and he’ll tell you that only a handful of baits—usually pricier ones—actually back up the claim. True suspension means you work the bait to the desired depth and if you do absolutely nothing at all, it will sit perfectly horizontal and still in that band of the water column. More often, what you get is a lure that kinda-sorta suspends. It hovers for a few seconds and then slowly sinks or floats back up. I’ve seen guys pull their hair out adding stick-on weights and changing hook sizes in an effort to achieve perfect neutral buoyancy.

In cold water, suspension is a big plus as it allows you to achieve a finesse presentation, keeping the lure in the strike zone as long as possible and imparting the subtlest movements without having to advance the lure far or fast. This gives sluggish fish more time to line up their shot and wait for the trigger, just like that pickerel under the ice. In the perfect scenario and circumstances, a suspending jerkbait is hard to beat, but good pickerel water doesn’t always provide that perfection.

Hang Time Bass fishermen hate chain pickerel because they’re often more aggressive than the bass. That equates to a lot of bitten-off jigs, soft plastics, and hardbaits. When the water warms up, that aggression is a plus if you’re a pickerel nerd like me.

Following ice-off, I commonly find pickerel suspended in deeper water relatively close to the shallows. The problem with suspending jerkbait is that they don’t play well when your depth range frequently changes. A bait that might hang at the perfect depth in 8 feet of water might be sitting right on the bottom in 4 feet. Naturally, your retrieve style and cadence can help make adjustments, but still, pickerel water tends to be weedy, reedy, and full of wood–none of which play well with two or three treble hooks. This makes paying up for good suspending jerkbaits just for pickerel a tough pill to swallow. But watching that pickerel on the ice gave me an idea. Instead of running pricey hardbaits I cringed when I lost, I switched over to a very simple tactic—a jig under a bobber.

I haven’t reinvented the wheel here. In fact, the tactic is called “float-n-fly” and was popularized in the smallmouth scene many years ago. True float-n-fly, however, is usually done with a specific style of float with a synthetic or hair jig hanging below it. The idea is that in cold water, the jig suspends at any depth you want and “breathes'' even when you’re not imparting action. All I did was swap out the hair jig for a soft-plastic paddletail swimbait and get cheap with the bobber.

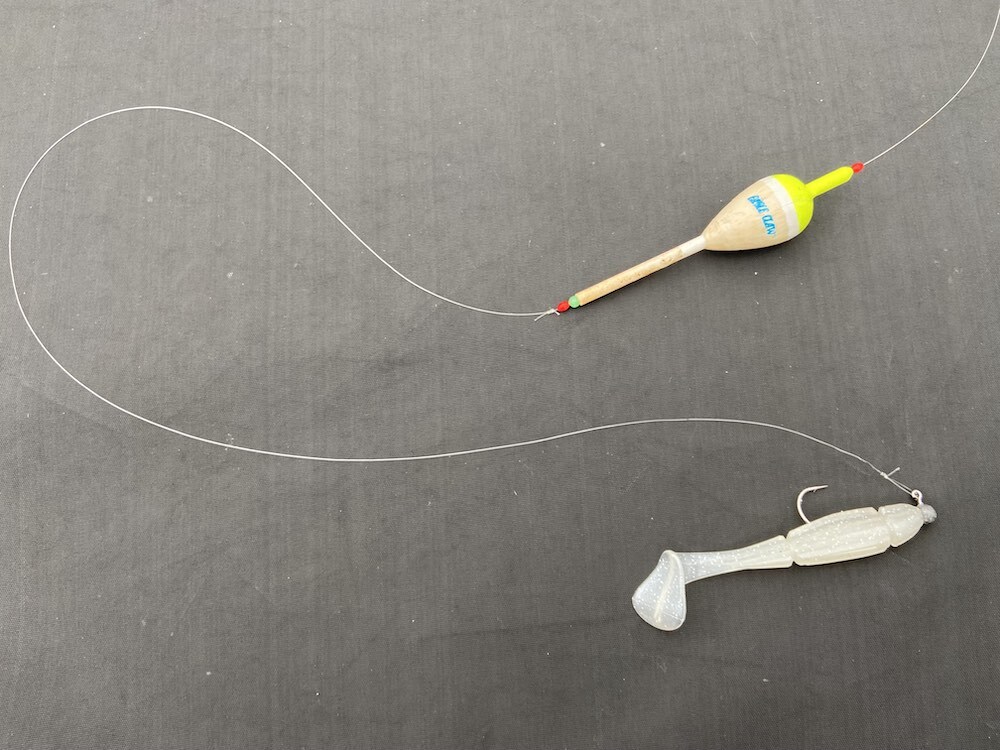

Float-and-fly is really designed to reach suspended fish in open water with minimal snags, but many of my favorite pickerel ponds and lakes are loaded with structure and overhanging trees. For that reason, I use the cheapest slip floats I can find—the neon Eagle Claws or Wal-Mart’s house brand work just fine. I’ll place a rubber bobber stop both above and below the float on the main line before splicing on an 18- to 24-inch leader of 15-pound fluorocarbon. I also buy the value pack of jigheads because I expect to lose a few each time out. While big pickerel are fighters, you don’t need tungsten heads and triple-strong hooks to land them.

I always tie on my jighead with a Rapala loop to give it more range of motion and action. My favorite baits to tip it with are the Keitech Swing Impact or 13 Fishing Churro, however, any 3- to 4-inch paddletail will work. The two bobber stops keep the float from sliding over the splice between the leader and main line where it could potentially get stuck, but the rig makes adjustment a cinch. The minimum depth you can fish is just deeper than the length of your leader; slide the top bobber stop up and you can hang that bait at 10 feet or more. Regardless of the water depth you’re targeting, you end up with bait that will suspend perfectly where you want it and let you make quick adjustments to compensate for weed tops or wood.

Wait Them Out I fire off a cast and do nothing for at least 30 seconds. The action and vibration of the bait falling to depth is often enough to draw a strike if a pickerel is close, or at least to get one's attention. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen that float drop 10 or more seconds after the bait settles. But if it doesn’t, patience is a virtue. Don’t pull the float ahead 2 feet. Instead, pull it 6 or 8 inches, just enough to make the bait rise and kick a couple times. If that doesn’t draw a strike, wait again before moving the float. Yes, it’s a slower process than summertime fishing, but I believe it draws more strikes—and keeps you in the zone longer—throughout the course of a day than using only jerkbaits.

The biggest question I get is about bite-offs. A long jerkbait is much harder for a pickerel to swallow, and they T-bone them most of the time, which keeps your line out of their teeth. You can add a short piece of bite wire to this rig, though over the years I’ve come to believe that doing so reduces the number of hits you’ll get. The more natural the swimbait looks and the more fluidly it moves, the better.

Occasionally I will get bitten off, and the odds increase significantly once the water jumps above 50 degrees, but I’ve noticed that when the water is really cold, the fish tend to grab and hold prey in the front of their mouth longer. Most of the time my jig ends up neatly in the top jaw—a placement that makes it hard for them to bite the leader if you keep pressure on. Every once in a while I’ll get bitten clean off, but it’s easier to stomach losing a cheap jighead and soft-plastic than a $25 jerkbait, whether it’s to a fish or the shopping cart at the bottom of the pond.

Conversation