There’s a difference between book smart and bar smart. You may not be book smart, butthis seriescan make you seem educated and interesting from a barstool. So, belly up, mix yourself a glass ofLMNT Recharge, and take notes as we look at the most popular lake names in the country.Powered byLMNT.

As a kid, I took great pride in “The Simpsons” creators choosing Springfield, South Dakota, as the backdrop for their iconic cartoon.What’re the odds the world’s most famous animated sitcom was inspired by a town just an hour from where I grew up?Well, when I got a bit older, I learned they’re pretty damn slim.

There are 41 Springfields nationwide, which is precisely why Matt Groening selected this generic town for Homer and crew to call home. (Springfield is second only to Washington, of which there are 88 in the country.)

“In anticipation of the success of the show, I thought, ‘This will be cool; everyone will think it’s their Springfield.’ And they do,” Groening toldSmithsonian Magazinein 2012. “Whenever people say it’s Springfield, Ohio, or Springfield, Massachusetts, or Springfield, wherever, I always go, ‘Yup, that’s right.’”

For as unimaginative as town names are, bodies of water are even worse. Creeks are particularly bad, with21 states claiming “Mill Creek” as the most common stream moniker. “Spring” and “Dry” are a distant second and third, with Spring Creek as the lead name for seven states and Dry Creek as the top name for five.

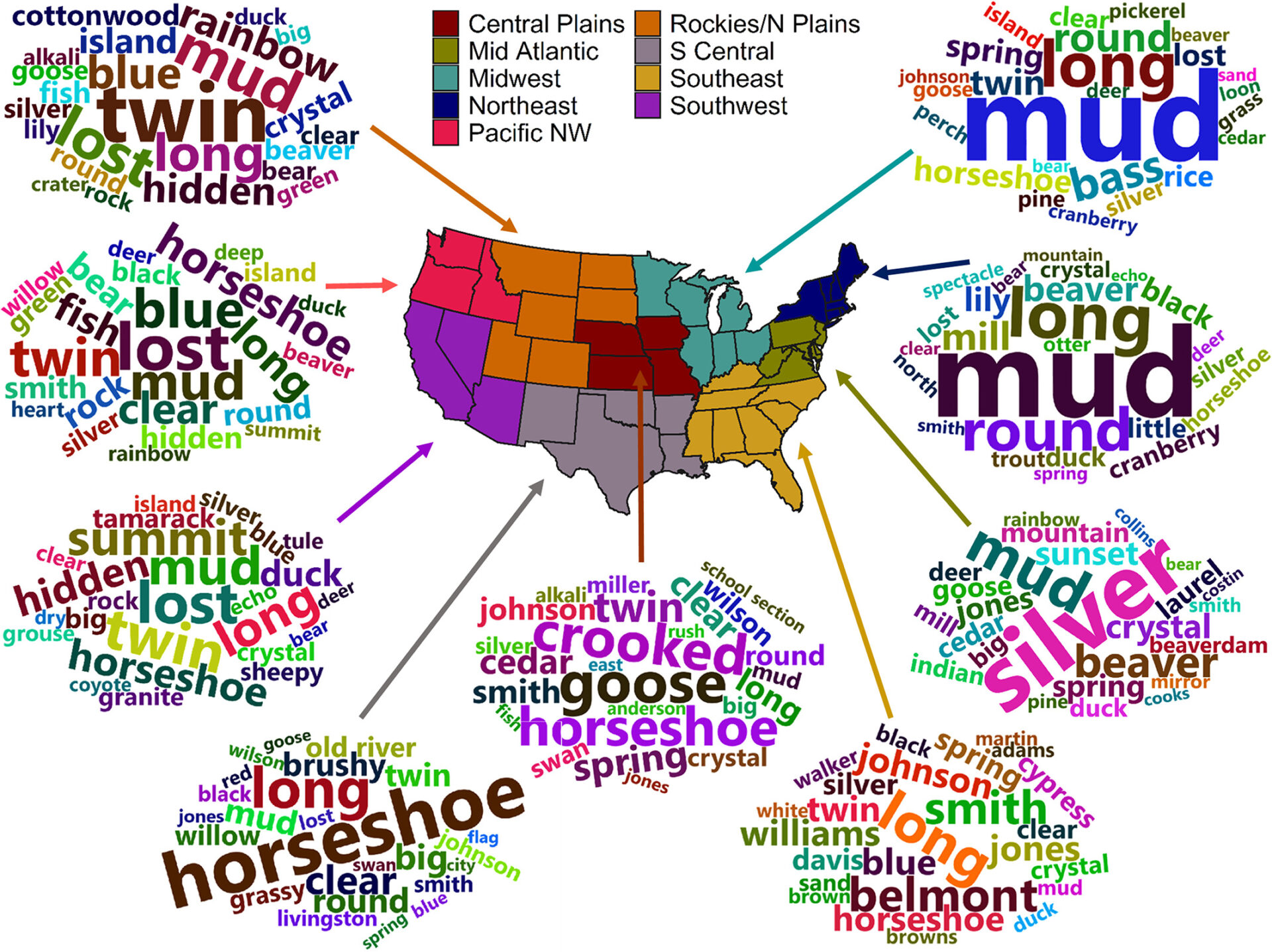

As you can tell, most creeks get a name that reflects its features—and lakes are no different. The most common lake names in the country are “Mud” (897 lakes), “Long” (400), “Twin” (400), “Horseshoe” (385), and “Round” (384). “Mud” is especially common east of the Missouri River, while “Twin” and “Horseshoe” are most popular in the West.

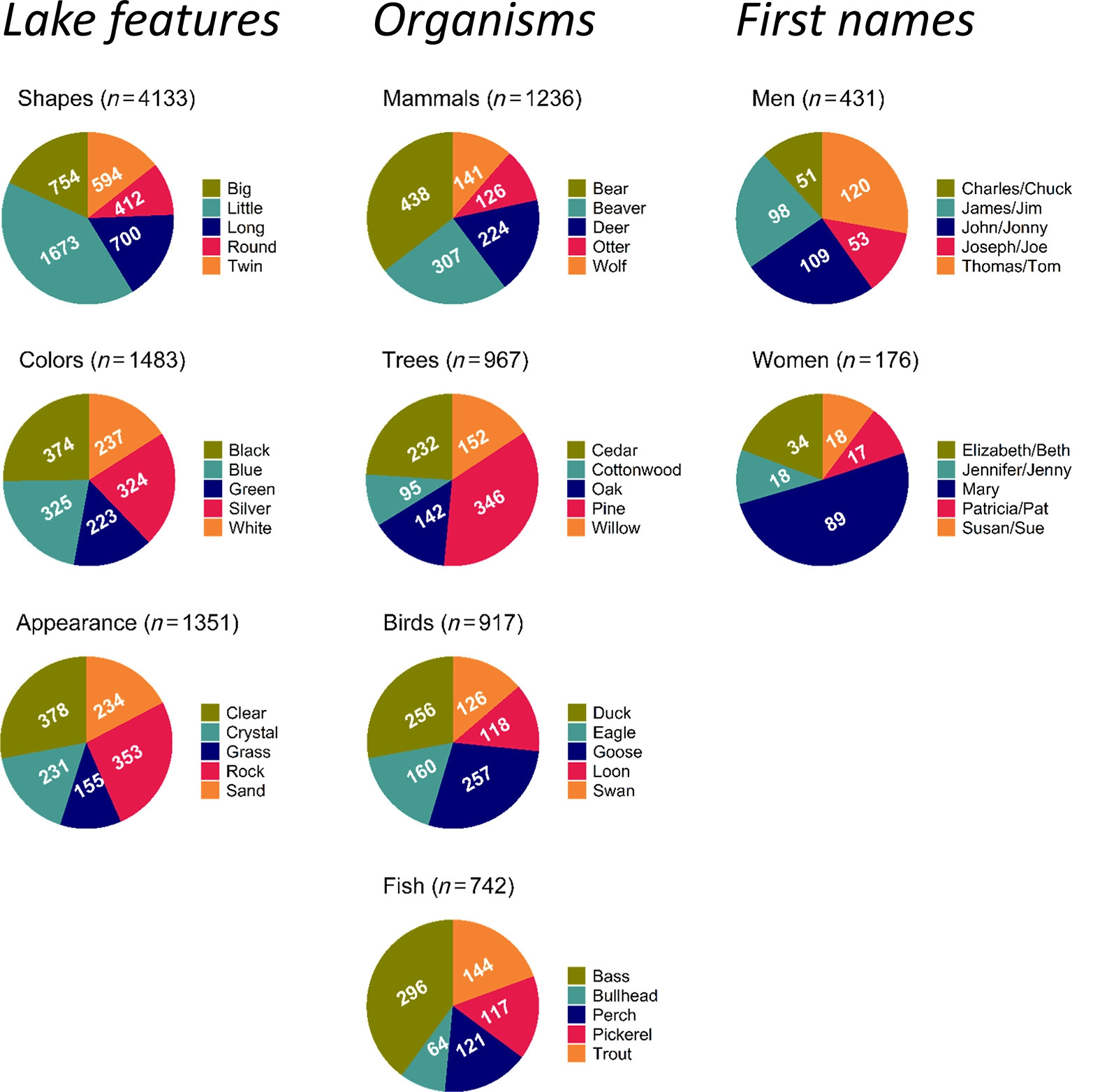

According to a 2020 study published by theAssociation for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography, lakes are most regularly named after the following features: shape, color, appearance, mammals, trees, birds, and fish.

“Little,” “Big,” and “Long” are the most popular lake shape names. “Black,” “Blue,” and “Silver” are the most popular colors. “Mud,” “Clear,” and “Rock” are the most popular appearances. “Bear,” “Beaver,” and “Deer” are the most popular mammals. “Pine,” “Cedar,” and “Willow” are the most popular trees. “Goose,” “Duck,” and “Eagle” are the most popular birds. And “Bass,” “Trout,” and “Perch” are the most popular fish.

Men’s and women’s first names make regular appearances as well. “Thomas/Tom,” “John/Jonny,” and “James/Jim” are the most popular male names for lakes. “Mary,” “Elizabeth/Beth,” and “Patricia/Pat” are the most popular female names for lakes. These numbers align with themost used birth names in the country. The top four names in America over the last century are James, Mary, John, and Patricia.

The two longest lake names in the country are both found in Montana: Clarence Cannon Memorial Watershed Structure Number 1 Reservoir and Little Siri-A-Bar Watershed Structure Number 1-5 Dam. The shortest lake names in the country are found in multiple states: Lake A, B, C, D, G, H, J, L, S, T, U, V, Y, and Z.

According to a2016 studyon lake nomenclature published inFreshwater Biology, there’s a direct correlation between lake size and how it’s named. Larger lakes are more likely to be [Lake] followed by [Name], while smaller lakes are more likely to be [Name] followed by [Lake]. Examples include all five Great Lakes: Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, Lake Huron, Lake Erie, and Lake Ontario. On the flip side, if I look at a map of the five small lakes closest to my house, I’ll find Fairy Lake, Mystic Lake, Lava Lake, Bozeman Pond, and River Rock Pond.

Amazingly, just 17% of lakes in the Lower 48 have an official name. It’s not difficult to get a lake named—literally anyone can do it. To suggest a lake name, you can submit a formal application to theU.S. Board on Geographic Names, Domestic Names Committee. It’s just a two-page document that asks for basic background information, such as lake location, evidence that it’s unnamed, and origin of proposed name. The committee says lakes can’t be named after a person or animal who is alive or has been deceased for less than five years; they cannot include a commercial name, be overly long, duplicate a nearby feature, include unusual characters, or be offensive.

Lake names actually serve a real purpose for data analysts. “From our research perspective of developing the LAGOS-US database, having lakes assigned an official name allows better tracking of continental-scale water quality because it provides useful information for confirming the identity of target lakes on digital maps,” according to a 2020 article inLimnology and Oceanography Bulletin.

So, I challenge you to do this: Find an unnamed local lake and submit an official name for it. (Or, submit arenaming applicationfor a lake with a derogatory moniker. According to a2015 study, there are 1,441 federally recognized places that use a racial slur in the name.) Maybe you’ll go for funny, like Beermug Lake in South Dakota and Too Lazy to Farm Lake in Tennessee. Or maybe name it after a local legend, like Drunken Charlie Lake in Washington and Greasy Jim Lake in Michigan. Or maybe you want a lake named after a less-boring animal, like Bigfoot Lake in Idaho or Unicorn Lake in Maryland.

Whatever you do, just don’t call it Mud Lake, Willow Lake, or Silver Lake. I’m really tired of asking my buddies, “Which one?” when they say they got a limit of walleyes at Horseshoe over by Springfield.

Feature graphic via Hunter Spencer.

Shop

Sign In or Create a Free Account

Related

Public Lands & Waters

The Most Instagrammed Outdoor Places in Each State

Public Lands & Waters

America’s Most Common Lake Names