There’s a difference between book smart and bar smart. You may not be book smart, butthis seriescan make you seem educated and interesting from a barstool. So, belly up, pour yourself a glass of something good and take mental notes as we look at one of history’s most famous tiger hunters.

Over the last three weeks, my family’s dogs have killed three of our four chickens. I often see the last remaining hen standing just outside the dog’s chain-link enclosure, staring at the drooling canines, unblinking, within 6 inches of certain death. I’ve named that chicken “Tom Hanks” because she’s a survivor. I’m thinking about renaming her “Jim Corbett.”

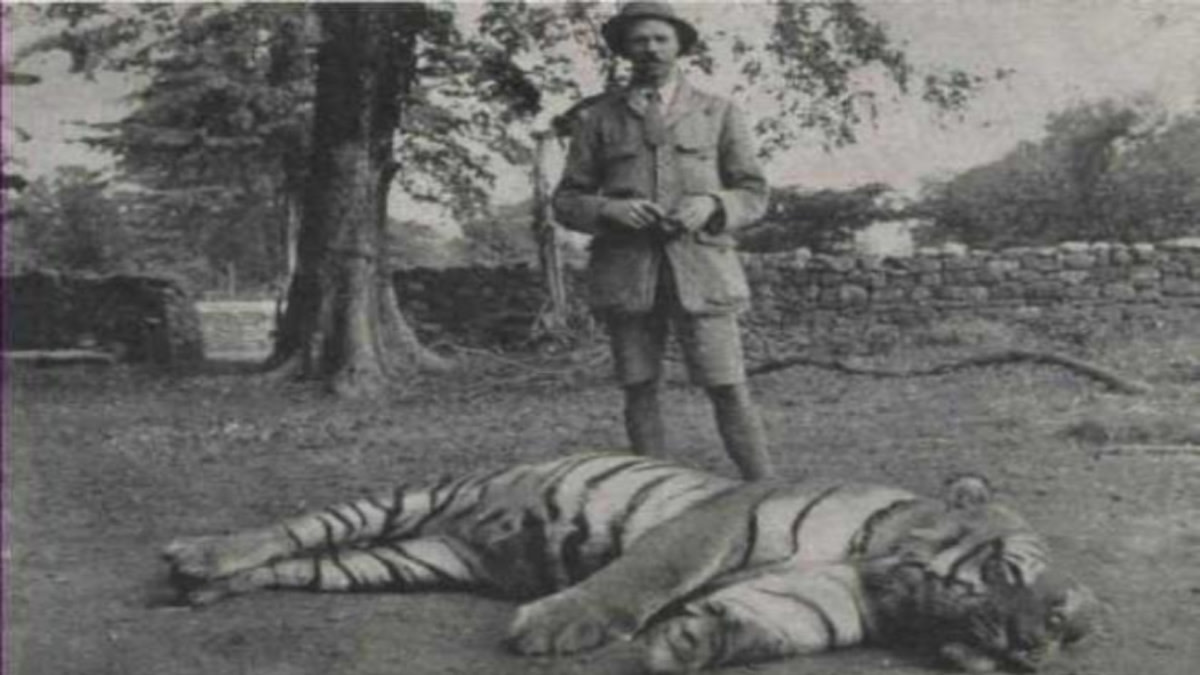

Jim Corbett, like that chicken, was ice cold. He stared death in the face and didn’t blink. He was like a real-life Chuck Norris joke or the personification of thatthug life meme. If you think I’m exaggerating, keep reading.

Corbett was born in India in 1875 to parents of Irish and English ancestry, and he spent the bulk of his 79-year life in India. During that time, he hunted and killed eight man-eating tigers and two man-eating leopards. He recorded the vivid details of those hunts in several books, the most famous of which isMan-Eaters of Kumaon.

In one chapter titled “The Chowgarh Tigers,” Corbett detailed his year-long quest from 1929 to 1930 to kill a female tiger that had killed at least 64 people over her five-year rampage. Like most of the tigers Corbett hunted, she and her sub-adult offspring operated in the northern Indian region of Kumaon.

Corbett killed her cub during his first trip to the area, but that only served to make the mauling more gruesome. As Corbett was careful to explain, tigers only become “man-eaters” when they are old or injured and cannot kill their natural prey. The elderly Chowgarh Tiger had relied on her offspring to quickly dispatch her human victims. Without that help, she wounded as many as she killed.

One young girl, for example, had been slashed from between her eyes, over her head, and down the nape of her neck, “leaving the scalp hanging in two halves.” She was still alive when Corbett got to her, and thanks to his first aid, she survived.

These and other grisly images must have been playing through Corbett’s head as he made his final stalk on the tiger. He’d lured her within striking distance by using a young buffalo as bait, but she fled when she became suspicious. He was forced to go into the jungle after her even though he could hear her growling in the underbrush and had no idea how close she was.

As Corbett stepped beyond a rock outcropping, he turned to his right and “looked straight into the tigress’s face.” She was lying a scant 8 feet away with her front paws stretched out and her head slightly raised. Across her face was a smile “similar to that one sees on the face of a dog welcoming his master home after a long absence.”

Corbett said later that the tiger’s culinary habits worked in his favor. Since she was a man-eater, she didn’t bolt past him or attack as soon as she saw him. She was content to take her time, even as Corbett slowly—ever so slowly—turned the muzzle of his rifle towards her giant head.

He had to make three quarters of a turn, and he couldn’t shoulder the rifle because he had eggs in his left hand (more on that later). The tiger’s eyes never left his, but as soon as the rifle was pointed at the animal’s body, he pressed the trigger.

At first, it seemed like nothing had happened. “I might, for all the immediate result the shot produced, have been in the grip of one of those awful nightmares in which triggers are vainly pulled of rifles that refuse to be discharged at the critical moment,” Corbett recalled.

The tiger remained perfectly still until, a fraction of a second later, her head slowly sank onto her outstretched paws and blood shot out of the bullet hole. Corbett’s shot had injured her spine and shattered the upper portion of her heart.

How to Hunt a Tiger

Corbett’s accounts sound fantastical, and he did have a flare for the dramatic. The victims Corbett highlighted are often young women, and they’ve usually had their clothes ripped off by the tigers. He claimed to possess a sixth sense for knowing when a tiger is near, and he described at one point how a bright blue necklace of a victim stood in “vivid contrast” to her crimson pool of blood.

Truth, however, is often stranger than fiction, and historians have largely taken Corbett’s accounts at face value. Corbett’s hunts were recorded by the British-Indian government, and the death toll of the man-eating tigers he dispatched is undeniable.

Hunters can also confirm the authenticity of Corbett’s approach to his craft. He said, for example, that courage and good marksmanship are not enough to kill dangerous, man-eating game: “Forethought, preparation, and persistence are indispensable to success,” he said.

Reading the signs of the jungle are among a tiger hunter’s most important skills. Corbett could identify an individual tiger by its tracks (what he calls “pugmarks”), interpret the sounds a tiger makes, and call in a tiger during the mating season.

A tiger hunter must also be able to use the wind to his advantage. Tigers do not know that humans have a weak sense of smell, so they always stalk their intended victim upwind. Knowing this, a tiger hunter can assume that if he must walk in the direction from which the wind is blowing, the danger likely lies behind him. Rather than walking backwards, however, Corbett recommended tacking back and forth across the wind to keep the danger to the right or to the left.

Other non-human jungle residents can also give a hunter essential information. In one account in a chapter titled “Robin,” Corbett described how he knew the location of a leopard and whether it was alive based on the calls of the axis deer in the area. Their vocalizations told him they could see the leopard and were alarmed, and their subsequent silence told him the cat had moved away.

Corbett relied primarily on information from the local villagers to locate a tiger in the vast jungles of northern India. As one of Corbett’s biographers Duff Hart-Davis explained, they were more than happy to assist Corbett in his endeavors.

A man-eating tiger kept impoverished villagers from working in their fields. People were afraid to go outside, and disease spread from unsanitary indoor conditions. “Terror would grip the community and bring the place to a standstill,” Hart-Davis wrote inThe Hero of Kumaon.

Once Corbett had identified a likely place to start his search, he tied a young buffalo as bait and determined, based on the landscape, whether to “sit up” or “beat.” In both cases, the tiger would kill the buffalo and relocate it. In a “sit up,” Corbett would sit over the kill and wait for the tiger to show itself. In a “beat,” he would recruit locals to scare the tiger out of cover and into his path.

If neither of those strategies worked, Corbett would attempt to stalk the tiger, as he did with the Chowgarh Tiger. He preferred to stalk tigers alone because “if one’s companion is unarmed it is difficult to protect him, and if he is armed, it is even more difficult to protect oneself.” At such times, he relied on his ability to read the jungle, his patience, and the ice-cold water running through his veins.

Corbett’s Guns

I can think of no hunting scenario that requires a more careful cartridge selection than a solo stalk of a man-eating tiger. Corbett used a variety of firearms and cartridges throughout his career, but his two favorites were an M98 bolt-action Rigby-Mauser in .275 Rigby and a .450-400 Double Barrel Nitro Express (D.B.N.E) manufactured by W. Jeffery & Co.

He considered the .275 a lightweight, long-range rifle, and comments that it is “not the weapon one would select” when dealing with a wounded cat. However, it is still more than capable of taking down a tiger. He killed two tigers in one evening with the .275, and it’s the gun he used to take down the Chowgarh Tiger.

He refers to his .450-400 as a “very efficient weapon, and a good and faithful friend of many years’ standing.” He used it successfully on the Chowgarh cub, the Bachelor of Powalgarh, the Mohan man-eater, Kanda man-eater, the Chuka man-eater and the Thak man-eater, according to Preetum Gheerawo writing inBehind Jim Corbett’s Stories.

The .275 Rigby would have produced comparable ballistics to a .308 Win. while the .450-400 could throw a 400-grain bullet over 2,100 feet-per-second.

Corbett’s .450-400 is currently in the possession of a private collector who purchased the rifle for a whopping $230,000, according to Gheerawo. The .275 was purchased in 2015 by the company that originally made it, John Rigby & Co., and is on display at their headquarters in London.Click here to check it out.

Hunter-Conservationist

Non-hunters sometimes have trouble understanding how hunters can love the animals they kill. I’ll leave that paradox for smarter minds, but it’s clear that Corbett exemplified it perfectly.

“A tiger is a large-hearted gentleman with boundless courage,” Corbett said. “When he is exterminated—as exterminated he will be unless public opinion rallies to his support—India will be the poorer by having lost the finest of her fauna.”

Corbett did not hunt man-eaters exclusively. Two of the tigers in “Man-Eaters of Kumaon” had never killed a human, though one was wounded and some worried it would become a man-eater. But Corbett’s reputation was based on hunting these problem animals, and he became one of India’s most prominent tiger conservationists.

In the 1920s, hebecame concernedabout overhunting and by habitat degradation. So, he helped establish India's first national park in the Kumaon Hills. The park was initially named the Hailey National Park but was renamed theCorbett National Parkin 1957.

Corbett was a budding naturalist even early in his career. InMan-Eaters of Kumaon, he includes detailed descriptions of birds, frogs, orchids, and snakes. He was holding bird eggs while stalking the Chowgarh Tiger because his egg collection was missing that particular species (he returned the eggs after surviving his encounter with the tiger).

Later in his life, he traded his rifle for a camera and used his photographs of tigers to spread awareness of the need for conservation. He did not condemn hunting, or even trophy hunting, but he was willing to change his pursuits based on the health of the tiger population. “The taking of a good photograph gives far more pleasure to the sportsman than the acquisition of a trophy,” he wrote.

Man-eating tigers are still hunted today. India only contains about 3,000 tigers, according to theBBC, but 40 to 50 people are killed every year. That’s a far cry from the estimated 1,200 people who were killed by the tigers Corbett hunted, but it’s still enough to (understandably) turn local populations against the species.

Some experts say that killing those problem animals is the best way to foster goodwill and help the species in the long-term.

“That’s the attitude necessary if you want to have a large number of tigers,” Ullas Karanth, a retired carnivore biologist at the Wildlife Conservation Society, told the BBC. “You can’t have everybody in the countryside turning against tigers because of one animal.”

Corbett dedicated his life to addressing these problem animals. For that, he’s remembered as both a hunter and a conservationist—not to mention a model of courage and grit for people and chickens alike.

To learn more about Corbett and his life, check out the books referenced here along with D.C. Kala’sJim Corbett of Kumaonand Martin Booth’sCarpet Sahib—A Life of Jim Corbett.

Shop

Sign In or Create a Free Account

Related

Hunting

The Man Who Hunted History's Most Lethal Tigers

Anthropology

The Most Secluded Humans on Earth