The number of hunters is declining across North America and the anxiety has reached a fever pitch among industry experts and wildlife conservationists.

At this year’s Shooting, Hunting, and Outdoor Trade Show—the largest of its kind in the world—the marquee press conference revolved around recruiting, retaining, and reactivating hunters in the United States.

“This is the show’s most important press conference,” Jim Curcuruto of the National Shooting Sports Foundation told the group of reporters. “This could change the world.”

But while the title of the press conference oozed with optimism (“A Million Hunters are the Way”), the tone remained grim. Speakers outlined various initiatives aimed at coaxing urban adults into the field, but it’s unclear whether these recruiting efforts will bear fruit.

The declining numbers are “pretty darn scary” and some believe that reversing the slide is impossible, said Joel Brice, Delta Waterfowl’s vice president of waterfowl and hunter recruitment programs.

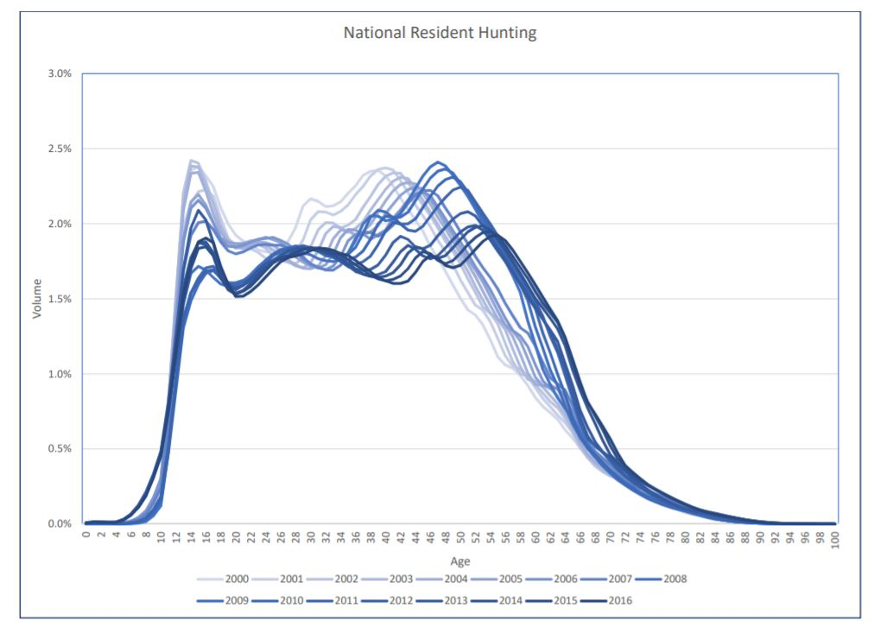

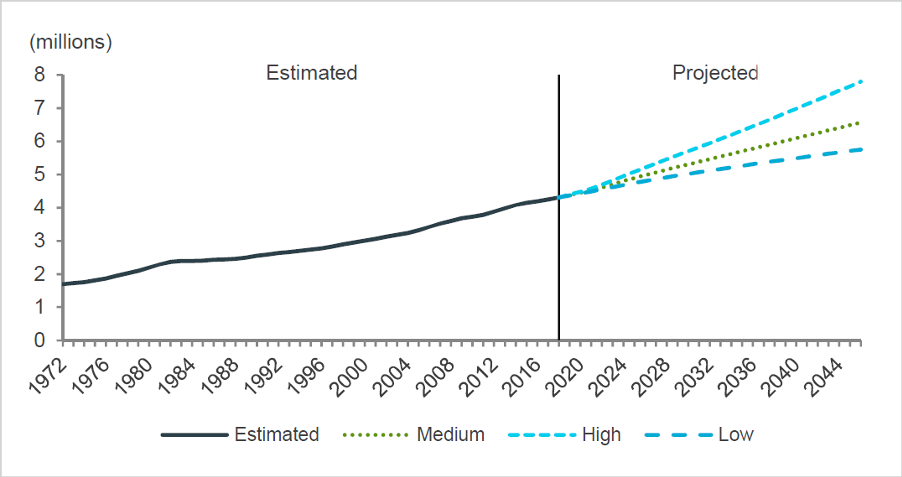

Urbanization, changing demographics, and aging Baby Boomers all contributed to a23%per-capita decrease in the hunting population between 1991 and 2016. If this trend continues, state wildlife agencies and conservation organizations will face “great challenges in revenue shortages, loss of political capital, and shrinking social relevancy” by 2032, according tothe Council to Advance Hunting and the Shooting Sports.

Conscientious hunters are aware of the problem, but no state has proven an effective, long-term recruitment strategy. Some might eventually show results, but so far only one North American jurisdiction has more hunters per capita now than it did 10 years ago: Alberta.

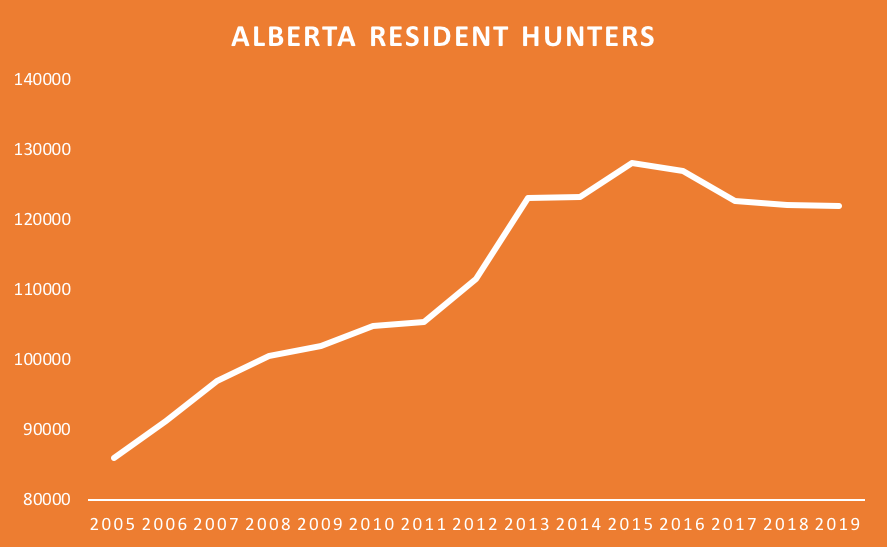

Alberta’s resident hunting license sales average has grown from approximately 115,000 to 122,000 in the last 10 years. It peaked at 128,000 in 2015, Jason Penner, communications advisor for Alberta Environment & Parks, told MeatEater. The per-capita growth rate on a 10-year average is positive, and Penner claims that Alberta is the only governing body in North America to show any such increase.

The numbers look even better on a longer timetable. The province only sold 85,932 resident hunting licenses in 2005, which means sales have increased by 42% (36,000 licenses) between that year and 2019.

The current highs don’t meet the historic high-water mark of about 160,000 resident licenses sold in the early 1980s, but Alberta’s data do suggest that the precipitous drop in sales continent-wide can be turned around.

Alberta Adventure

Provincial officials and conservation organizations have leveraged a wide array of strategies to boost the province’s hunting population. But one messaging point stands out to activists and hunters alike: the adventure of harvesting food.

Like in many Western states and provinces, game-heavy hunting grounds are less than an hour’s drive for most Alberta residents, but accessing and harvesting on those remote landscapes can be especially challenging. That’s exactly what many hunters are looking for.

“There’s no doubt that there is a portion of the population that is very keen on that kind of idea,” Todd Zimmerling, president and CEO of the Alberta Conservation Association, told MeatEater. “The challenge of ‘doing it myself.’”

Two such sportsmen are Steve Elliott and Dan Peacock. When asked for their best hunting story, both long-time hunters reveled in the treacherous nature of their experiences and focused not on the kill but on the harvest.

“The foothills of Alberta will eat your lunch. You could die out there if you’re not well-prepared,” Elliott, 68, told MeatEater.

During one trip along the Bull River in the 1990s, he shot a big mule deer in -20 degrees F weather and watched in dismay as the deer gathered enough strength to jump into the river and drown. The antlers were the only part that remained visible among the ice floes as it floated away.

Elliott considered alternatives (which included lassoing the horns while the animal passed under a bridge downriver), but he soon realized what he had to do.

“My friend Dan says, ‘Only one way you’re getting that deer out. You gotta go get him,’” Elliott recalled.

He stripped down, walked a half-mile in the frigid, shallow river, and managed to pull the carcass by its antlers back to the shore where another hunter had parked his truck with the heater blasting. While Elliott recovered in the truck, his hunting partners quartered the buck, and he brought it home to his family.

Harvest Your Own

The province has recruited and retained hunters like Elliott and Peacock, in part, by highlighting the challenge, adventure, and joy of harvesting wild game. Officials dedicated a separate website to hunting, angling, and trapping called “My Wild Alberta,” and the ACA has seen success recruiting new hunters using a website they call “Harvest Your Own.”

Zimmerling said the Harvest Your Own program started by reaching out to marketing experts who weren’t part of the hunting community. They realized that appealing to hunting tradition and heritage would not resonate with Albertans who had not grown up in the field.

“It’s really hard to convince a mom who’s never done this before to take her 8-year-old out and kill something,” he said. “That doesn’t click with someone who’s never done it before.”

Keeping these new hunters in mind, they tried to emphasize the aspects of the hunting experience that might appeal to anyone. Instead of featuring images of slain animals, for example, the Harvest Your Own website highlights Alberta’s natural beauty, the emotional benefits of hunting, and the challenge and reward of harvesting wild game.

“We start with an image of a nice roast and work backwards from there,” Zimmerling said.

It’s also a powerful message for retaining experienced hunters.

“I enjoy the adventure. I enjoy going to a place where there’s no one and just wandering to see what’s over the next hill,” Peacock said. “Having a rifle or a bow so there’s a possibility of bringing a meal back just adds another dimension to it. It’s a bonus to be a provider, to bring back meat.”

A Team Effort

These aren’t the province’s only strategies, of course. Regulation and policy changes over the last 10 years have allowed residents to access wild spaces more cheaply and easily.

You might be wondering if the province has simply dropped license prices in order to artificially inflate sales.Some states have done that. Penner admitted that the province has begun offering some senior and youth licenses at a reduced cost, but thedata since 2014indicate that adult licenses are responsible for the increase in sales (youth purchases have actually dropped slightly).

Some hunters might argue that Alberta’s population boom has driven increased sales more than the efforts of hunting-related departments and organizations. While it’s true that the province’s population has grown over the last 10 years, the population also grew while the number of hunters was shrinking in the 1990s. If population growth was the only factor, one would expect the hunting population to have been steadily increasing for the last five decades.

Rather than simply reducing the cost of licensing, the province has used a variety of strategies to increase real participation.

Penner identified strong youth recruitment through organizations like theHunting for Tomorrow Foundationand theAlberta Hunter Training Instructors Association. These groups have worked together to implement a variety of youth programs and hunting camps, including a hunting mentorship program.

Alberta also offers an abundance and diversity of special license draws for big game species across the province, with a significant increase in tags available for elk and moose in prairies and parkland areas. Over-the-counter tags and under-subscribed special licenses are available for whitetail deer, bighorn sheep, mule deer, moose, and elk every year.

Mentorship and tag programs no doubt contribute to the province’s success. But conservationists, provincial officials, and hunters say that two priorities have set Alberta apart from other states and provinces: access and cooperation.

Alberta offers a great deal of both public and private hunting grounds, but Elliott noted that much of the public land is difficult to access and even more difficult to hunt. The best land is often held privately by individuals or is leased out by the government to ranchers. But unlike many states with little huntable public land, Alberta does not allow landowners or land leasers to charge a fee to hunters.

“[The province] has done a very good job of preventing the pay-to-hunt model,” Zimmerling said.

In addition, conservation organizations have banded together to purchase hunting sites for public access. The ACA put togethera guideof these sites for prospective hunters, including over 800 locations spanning 300,000 acres that do not require hunters to secure permissions.

These purchases were possible, Zimmerling explained, through close-knit cooperation among conservation organizations.

The ACA is a member group consisting often conservation associationsthat run the gamut from education, to outfitting, to species-specific advocacy. This diversity of expertise and audience allows the nonprofit to run initiatives that would be impossible for one organization working on its own.

“Because each of these groups sits on our board there is a significant amount of coordination with respect to promotion of hunting, mentoring programs, training programs, etc.,” Zimmerling said.

Ultimately, Alberta’s success cannot be attributed to one or even two factors. It required a focused, coordinated effort between the government, landowners, hunters, and conservationists to capitalize on the province’s abundant natural resources to recruit and retain hunters. Increased access, mentorship programs, tag policies, and effective marketing have all played a critical role, and officials hope to maintain the success in the years ahead.

On the Ground

Peacock and Elliott have noticed the uptick. Elliott told MeatEater that he started to see more hunters starting even in the early 2000s.

“There were spots in the 1990s where we wouldn’t see another person all day. That was common. We wouldn’t only be the first people in the field—we’d be the only people in the field,” he said. “In 2003, we went to the usual spots, and there were already guys in there.”

People are drawn to Alberta’s hunting grounds in increasing numbers for the same reason Peacock keeps going out: not for the thrill of the kill but the chance to slow down and enjoy the natural world.

“There’s something almost spiritual, if you will, that I find hugely pleasurable,” Peacock said. “It gives a person time for their mind to stop racing and just enjoy what God’s created. I see the synchronicity in all of it, and it just kind of makes the world make sense.”

Feature image via Captured Creative.

Shop

Sign In or Create a Free Account

Related

Big Game

Hunting Is Safer Than Ever

Big Game

Hunting is Declining Across North America—Except in Alberta. Here’s How.