Cartooning Conservation: Ding Darling, Ed Anderson, and Saving South Florida

Wandering around ICAST, the big fishing industry tradeshow in Florida a few years ago, I came around a corner and saw a burly man in front of an easel. I watched as he set down his paintbrush, slung a ukulele off his back, and absentmindedly began strumming a tune toward the six-foot wide, half-finished painting of a tarpon.

Though early in the composition, the creator’s identity stood out in bold brushstrokes, loud colors, and the slightly comic musculature of the tarpon. Even the ukulele was painted with big, wide Megalops scales. I waited until the serenade was complete then introduced myself.

Ed Anderson and I went on to collaborate on several projects. Last May, Ed mentioned that he had been selected as this year’s artist-in-residence at the Ding Darling National Wildlife Refuge in Sanibel Island, Florida. Neurons began snapping together in my brain.

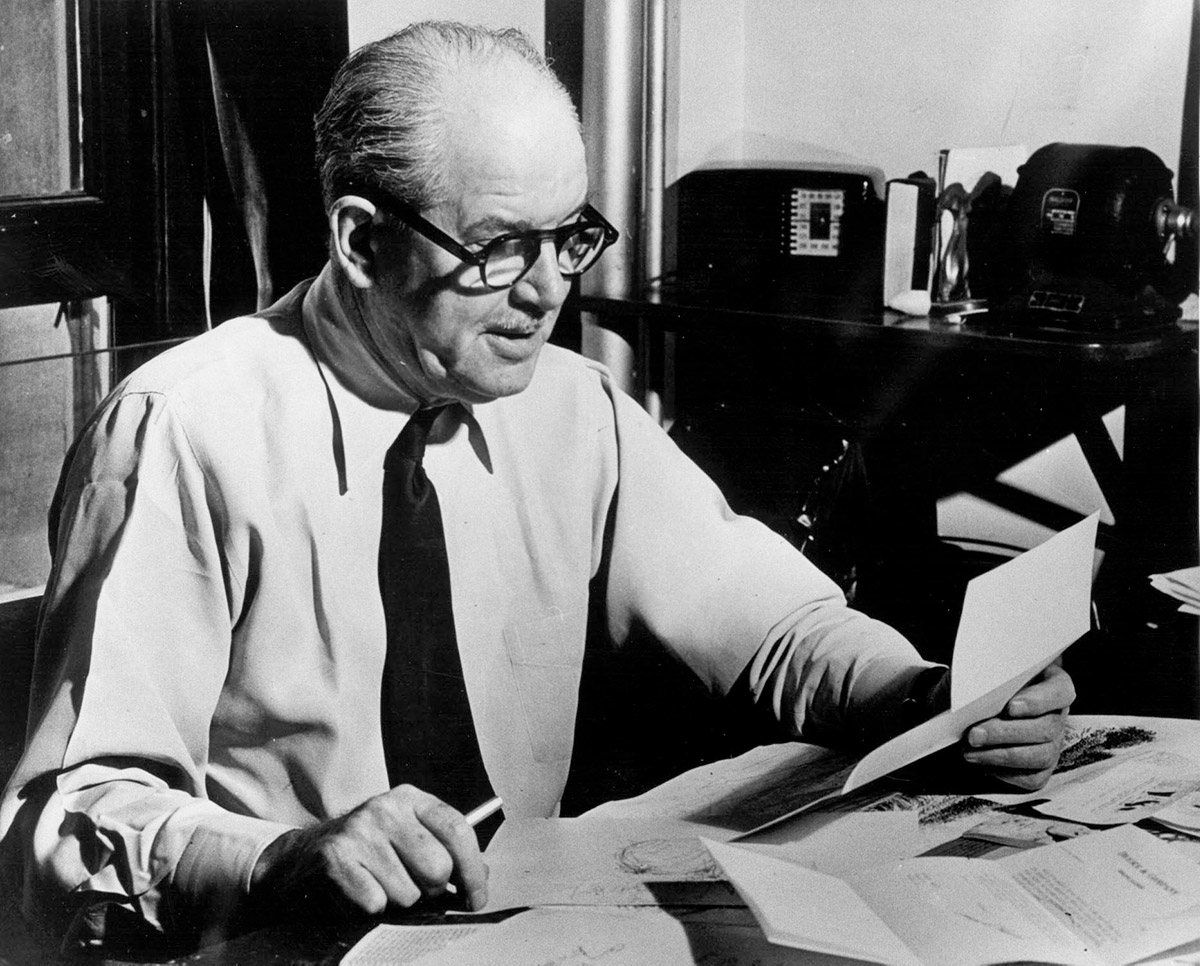

If you hunt or fish, you ought to have heard of Jay Norwood Darling, better known by his pen name—“Ding.” Born in 1876 and a cartoonist by trade, he grew to national prominence and syndication during the 1920s and ’30s in part because of his poignant messages in support of the new and growing conservation movement. He advocated for many of the tenets of wildlife conservation we know today— license fees, excise taxes on sporting equipment, reasonable seasons and bag limits, state wildlife management agencies, and wildlife refuges.

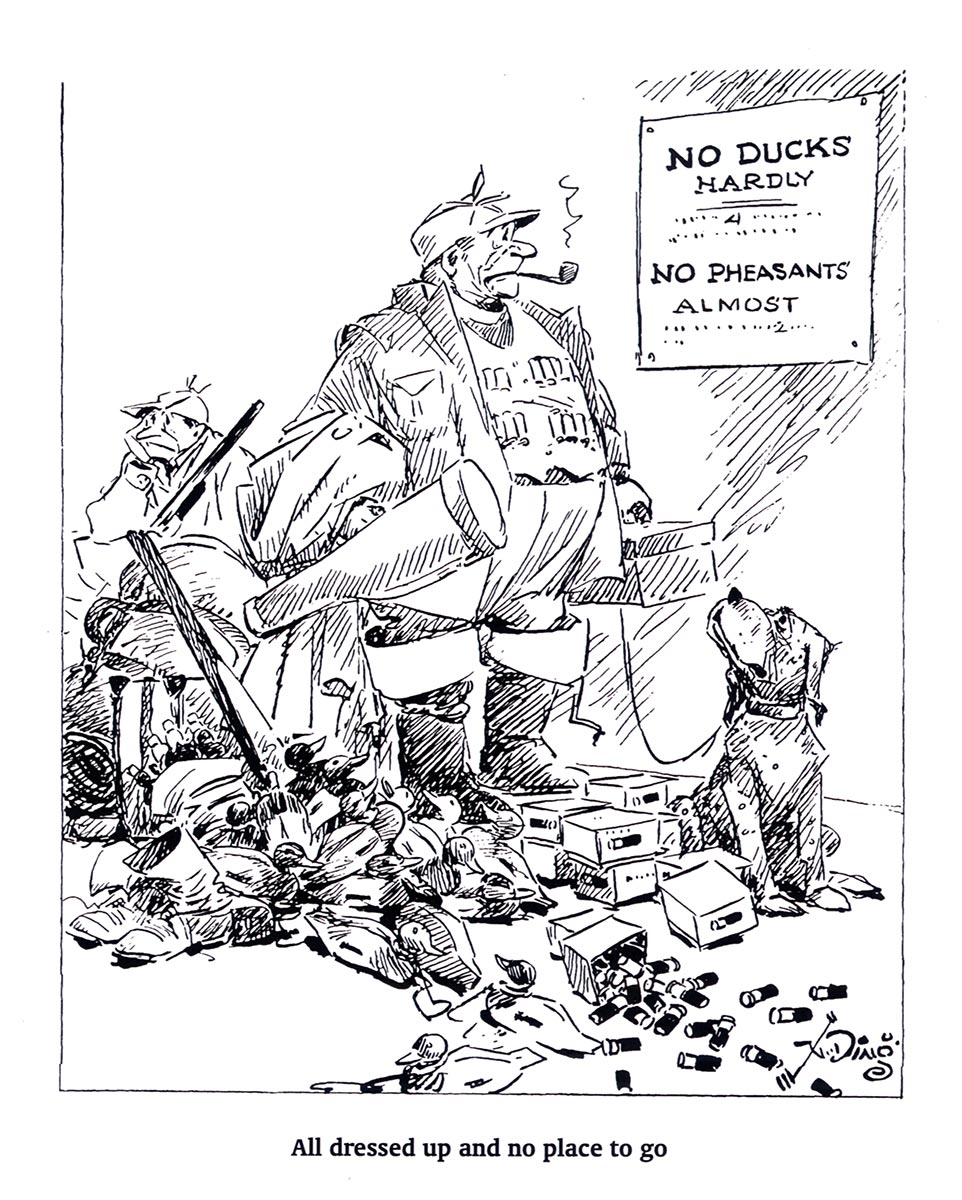

Ding suffered through the dark ages of wild animal populations in North America. The era of unregulated market hunting ended in 1900 with the Lacey Act, but the dire poverty and chaos of the Dust Bowl, the Great Depression, and World War I kept accelerating many species’ tailspin. Game animals we now consider over-abundant in many areas—Canada geese, whitetail deer, turkeys—were in danger of blinking out forever. And yet, many sportsmen still failed to realize that they bore any responsibility for this crisis—or that they could do anything to change it.

Though Darling identified as a life-long Republican, President Franklin Roosevelt appointed him chief of the new U.S. Biological Survey in 1934, a precursor to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Disliking Washington, D.C., and frustrated with congressional refusal to fund conservation work, Darling only lasted 20 months. But in that time, he formed a functional agency, strengthened the federal appetite for conservation, and implemented the Duck Stamp Act. He even designed the first-ever stamp for the Federal Duck Stamp Program. Duck stamps have generated more than $750 million to buy, lease, and restore 5.3 million acres of wetlands habitat and remain the most important funding source for waterfowl conservation. Think about that, and Darling, when you press that stamp to your license this fall.

Before he left government for good, Darling convinced FDR to let him convene a massive cohort of conservationists. This forward-thinking brain trust worked out practical solutions to advocate, pay for, and execute sound wildlife management. Out of that 1936 conference grew the General Wildlife Federation, which became the National Wildlife Federation, a perennial voice for the constituency of Americans who care about wild animals and wild places. Darling served as the first president of the organization, which now includes more than 6 million members.

In his later years, Darling’s frustration with the slow progress of conservation against the rising flood of development and pollution resulted in disenchantment with the federation. But he continued to be a strong voice for environmental protection through his syndicated cartoons until his retirement in 1949 after 43 years with the Des Moines (Iowa) Register. At their height, his cartoons were syndicated in more than 100 newspapers. He won the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartoons twice, in 1924 and 1942.

Darling spent many winters drawing and painting on Florida’s Sanibel and Captiva Islands. In 1945, he convinced President Truman to designate 6,200 acres of the area’s mangroves and seagrass beds as a national wildlife refuge, successfully blocking a massive residential development project. In 1967, five years after Darling’s death, the refuge was renamed in his honor.

Ed Anderson visited the Jay Norwood “Ding” Darling National Wildlife Refuge before he was even a year old. Born and raised in Minneapolis, Ed frequently visited his surrogate grandparents on Sanibel throughout his childhood, and his parents later moved there as well.

Like Darling, Ed’s work draws on his experiences of chasing and appreciating fish, game, and the habitats where they thrive. His success has been somewhat meteoric. Ed’s first published work graced the cover of Gray’s Sporting Journal, an honor some artists strive for decades to attain. He got that cover three times in his first year. Ed went on to work with other magazines, outdoors brands, and non-profits as he continued to develop and refine his contemporary, pop art style, as well as his journal series that read like outdoor adventure comics. His work now appears in galleries in Cape Cod, Mass.; Park City, Utah; and Polson and Big Fork, Montana. He travels often for art projects with his wife, Rebecca, and rambunctious twin, 7-year-old daughters, Aubrey and Elyse.

Though aware of Darling through his many trips to Sanibel, when Ed’s own career veered toward conservation, he started to really grasp the man’s significance.

“I’m inspired by his lifestyle and teachings and the passion and the views he had,” Ed said. “He was pretty outspoken and obviously he was very well celebrated because of it.”

Ed appreciates the often-humorous tone of Darling’s drawings, which appealed to broader audiences than other, more “fine” artistic styles. That made for mass appeal—and effect.

“Ding has this tone in a lot of his cartoons about the how wildlife doesn’t have representatives or they’re not constituents of the politicians. He had a pretty big disdain for the political class, too.”

Ed shares that disdain and remains politically agnostic for the most part. Also like Darling, however, he sees many conservation issues as somehow separate, clear-cut, above the fray. The toxic freshwater being dumped from Lake Okeechobee into Pine Island Sound and Sanibel Island, for example, transcends partisanship.

“I think that it’s been terribly managed,” Ed said. “I mean, maybe I’m talking out of both sides of my mouth but yeah, there are some issues that I don’t see too much gray area.”

Through his residency, sponsored by the Ding Darling Wildlife Society, Ed hopes to call attention to the wretched state of South Florida’s water management. Massive cyanobacteria and red tide blooms fueled by freshwater discharges from Lake Okeechobee have devastated the refuge’s marine ecosystem. In the summers of 2016 and ’18, hundreds of tons dead fish, dolphins, manatees, shrimp, crabs, and all manner of sea life washed up on the beaches of Sanibel and the refuge. In July 2018, locals discovered a dead, 21-foot whale shark, apparently taken down by the oxygen-stealing red tide.

Birgie Miller is the executive director of the Ding Darling Wildlife Society and helped organize Ed’s artist residency.

“That’s really what Ding Darling started through his editorial cartoons that Ed is kind of playing around with, trying to educate people about what they’re doing to our environment,” Miller said. “And that’s why he started the Duck Stamp because they were just killing so many of them. [Darling said] try to control it and be responsible so that you can hunt for generations afterwards.”

Darling’s eponymous refuge and wildlife society are kicking off next year’s 75-year anniversary with Ed’s residency, followed by a visit from the current duck stamp champion, Scott Storm—a celebration of artistry to create support and funding for wildlife conservation.

“That was all started by Ding,” Miller said. “He got people involved through his cartoons.”

Ed has also thrown in with Captains for Clean Water, a group protesting Florida’s water management and seeking solutions. They’d talked about doing a T-shirt for some time so when we were down there this summer producing an episode of MeatEater’s new fishing show, Das Boat, we decided to make it happen.

We (mostly Ed) worked hard to produce this mean-looking tarpon design, an embodiment of the resilience of Florida’s aquatic ecosystems, and an emblem what we stand to lose. Tarpon, what many anglers might call the greatest sportfish in the world, are in trouble. So are snook, my personal obsession. Redfish and sea trout have, by and large, already disappeared from the refuge.

MeatEater printed Ed’s design on a tropical blue, light cotton hoody, perfect for staying cool while wading flats or rivers. We are donating all profits to Captains for Clean Water to aid in their fight to keep all those fish around. Take a look and consider buying one to lend support and solidarity to this cause.

Ding Darling was more of a three-piece, pinstriped suit kind of guy. It was a different age. But I can only think the architect of the National Wildlife Federation and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and Pulitzer Prize-winning comic artist would look approvingly on the use of cartoons for conservation.

Conversation