How Early Hunters Ran Down Deer on Foot

I jogged two miles this morning. I’m not bragging—deep down inside I know my hunting predecessors must be terribly ashamed of me. My knees hurt. My back ached. My shins burned. I couldn’t imagine running down and killing an energetic tortoise on foot, let alone a healthy antelope or deer. But according to many word-of-mouth accounts and a growing mound of anthropological evidence, that’s exactly what some hunters did for thousands of years.

“In winter, after the first snow, we frequently saw three or four Indians hunting deer in company, running like hounds on the fresh, exciting tracks,” John Muir wrote in his late 1880s“Wisconsin.”“The escape of the deer from these noiseless, tireless hunters was said to be well-nigh impossible.”

In his best-selling book“Born to Run,”Chris McDougal wrote about the indigenous Tarahumara peoples of Mexico doing the same. “One explorer swore he saw a Tarahumara catch a deer with his bare hands, chasing the bounding animal until it finally dropped dead from exhaustion.”\

Utah State University Professor Emeritus and Navajo expert Barre Toelken recounted a similar situation, as cited in Richard Nelson’s book“Heart and Blood.”“When the deer is finally caught he is thrown to the ground as gently as possible, his mouth and nose are held shut, and covered with a handful of pollen so that he may die breathing the sacred substance.”

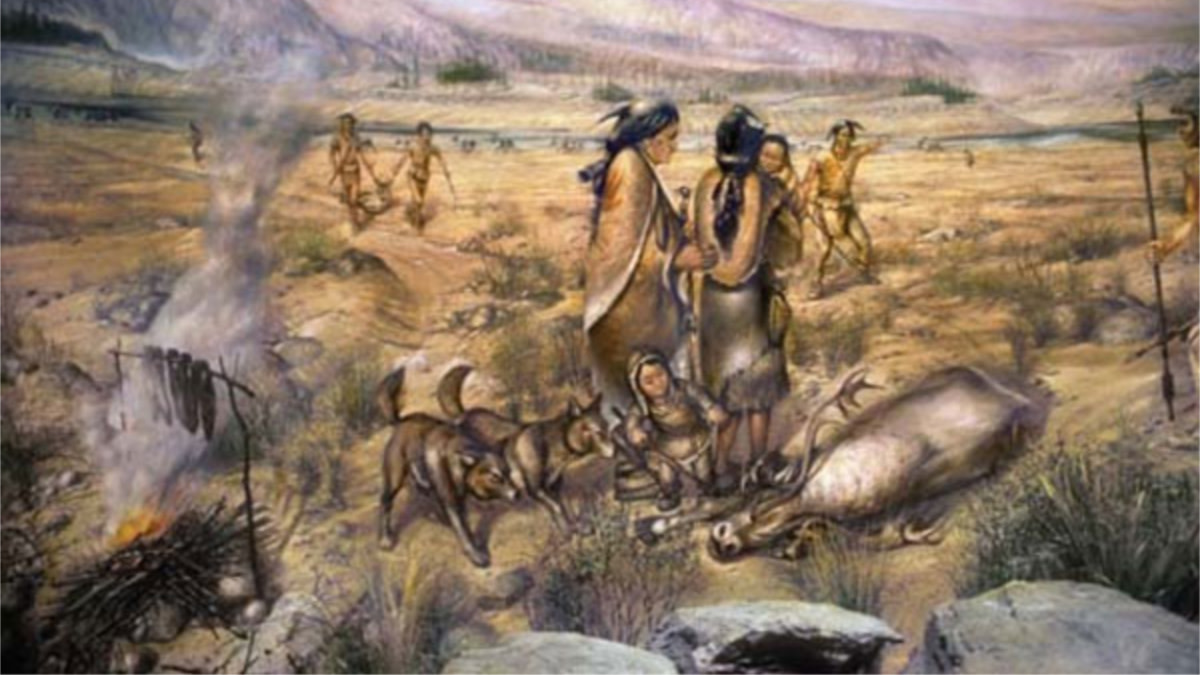

How can an animal so fleet of foot, so swift, so shifty, and so untouchable possibly be run down on foot? The answer seems to lie within our ancestors’ anatomy. Some anthropologists believe that what separated the trajectory of ancient humans from other hominids of the time was a certain set of physical adaptations that allowedHomo sapiensto run for long distances. This idea has become known as“The Running Man Theory.”

The development of the Achilles tendon, arched feet, large gluteus maximus, and head-stabilizing tendon called the nuchal ligament were crucial. They uniquely prepared our species to run great distances on two feet while staying cool through our one-of-a-kind perspiration system. This combination allowed early humans to literally run animals to death, even before more efficient weapons were invented.

It’s hard to fathom, but if you consider the parable of the tortoise and the hare, you can begin to see how this is possible. As we all know from the childhood story, the hare is exceptionally fast over a short distance, but the tortoise’s slow and steady pace wins the race. The same factors are at play between human endurance running compared to the speed of a deer.

Harvard researchers have examined how human runners and ungulates tire differently. As explained in “Born to Run” by Chris McDougal, what they found is that while deer can reach higher speeds than humans, this added speed requires heavy-breathing and panting. Although slower, humans can carry on a reasonable speed for much longer periods without reaching a high breathing rate. Again, it’s all thanks to perspiration.

“To run an antelope to death, Lieberman determined, all you have to do is scare it into a gallop on a hot day. ‘If you keep just close enough for it to see you, it will keep sprinting away. After ten or fifteen kilometers worth of running, it will go into hypothermia and collapse’,” McDougal wrote.

This isn’t just theoretical. As recently as the 1980s, Kalahari bushmen were witnessed successfully participating in what has come to be known as “persistence hunting.”

About a decade ago, inspired by McDougal’s book, a group of men set out in eastern New Mexico to test the theory by attempting to run down a pronghorn. Although they didn’t kill the animal, after running the antelope nearly 20 miles, they allegedly came “very close.” As described by Charles Bethea in a story forOutside Magazine,one of the runners could have hit and killed the pronghorn with a rock.

“Their goal was to prove a point about their evolutionary advantage,” Bethea wrote. It seems they did just that.

And so I sit here now, still sore and aching, but with new hope for the unrealized potential of my human bioengineering. I better start jogging regularly (or justpractice with my bowmore).

Shop

Sign In or Create a Free Account

Related

Anthropology

How Early Hunters Ran Down Deer on Foot

Public Lands & Waters

Oklahoma Is Just the Latest State to Crack Down on Nonresident Hunters