Knocking a fast-flying bird out of the sky with a shotgun is one of the greatest challenges in hunting. Doing it once or twice a season is tough enough; doing it consistently from one year to the next, with a variety of species, can seem damn near impossible.

In fact, achieving a base level of proficiency with a shotgun is much more difficult than a rifle. That’s because wingshooting, the art of hitting flying targets with a shotgun, occurs on a much more instinctive level.

When shooting a rifle, there’s usually time to adjust your form and to correct mistakes before they happen. With a shotgun, there isn’t. Once your quarry flushes into the air, you have seconds at most to shoulder your piece and fire.

Lots can go wrong, and it usually does. You grip your shotgun too tight and it twists off target as you pull the trigger. Or you don’t get a proper lead by “swinging” the shotgun through the fast-moving target and your load passes through the vacated airspace in the bird’s wake. Or you simply miscalculate the speed, angle, and distance of the bird and your shot is wildly off.

The only way to get really good with a shotgun is to spend a lot of time shooting clay targets at the range. It takes dozens of hours of practice and hundreds of rounds of ammunition just to get good enough that you don’t totally suck.

Or as my bird hunting buddy Ronny Boehme puts it, “If you can’t hit a clay target, you’re never gonna hit a bird.”

Here’s a quick checklist to keep in mind the next time you have a nanosecond or two to drop a ruffed grouse that’s about to fly into a thick patch of….oops. He’s gone.

Grip

Not too tight, not too loose. With the trigger hand, think of a comfortable handshake. You want your thumb rolled over the top of the grip, not resting on top of it. When it’s time to fire, use the fleshy part of your finger tip, just above the last joint, to squeeze (not pull) the trigger. Your forearm hand should cradle the forearm of the shotgun comfortably, with a gentle grip.

Shouldering the Gun

When raising the shotgun to fire, the forearm hand pushes the gun out and up toward the target. The trigger hand simply raises the stock up to your face. All the while, remain focused on the target. Let the bead of the shotgun enter your sight picture without moving your eyes to find it. Unless you’re shooting directly overhead, your weight should shift to your front foot as you “lean into” the gun. For overhead shots, keep weight on rear foot and move forearm hand toward the body and the stock of the shotgun for a more comfortable position.

Foot and Body Position

Physically positioning is tough to master. At a shooting range, you’re typically on flat ground with plenty of time to assume the proper stance. In the field, game has a way of flushing at the worst times: while you’re over rocks, crawling under downed trees, or trying to extricate your hat from a grabby patch of briars.

The trick is determining how long you have to prepare for the shot, and then do as much as you can to assume the proper position before it’s too late.

Ideally, you’ll end up with your front knee slightly bent and rear leg straight. For foot placement (right-handed shooter) imagine that you’re standing on the face of a clock with your target out beyond the 12 o’clock position. Your left foot should be pointing to about 11 o’clock, your right foot to about 2 o’clock. Heavyset shooters tend to find their most comfortable position by squaring off to the target even more, lessening the angle.

Making the Shot

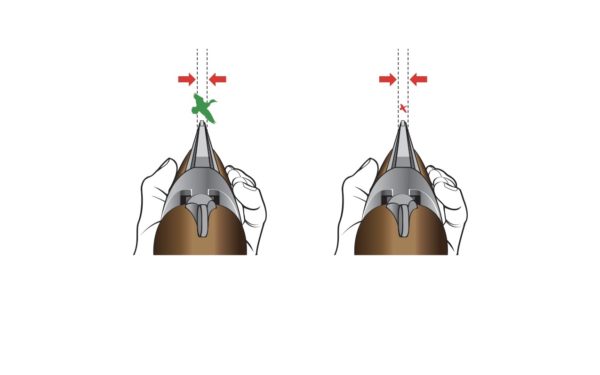

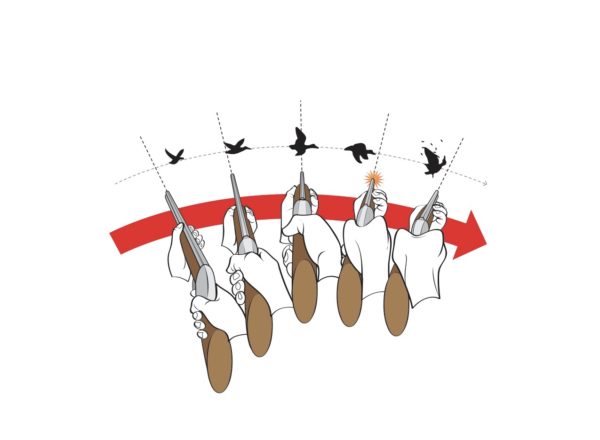

Here, of course, is where things get tricky. You’re trying to connect pellets that will be flying at about 800 miles an hour with a target that might be going 40 or more miles per hour. Causing the two things to collide in mid air (or on the ground, in the case of rabbits) requires significant skill. Most hunters use a shooting method called swing through, or pass-through.

The gun is inserted into the hunter’s sight picture behind the traveling target. The hunter then swings the shotgun through the target’s flight path in a smooth arc. The swing continues through the target in a continuous motion, with the muzzle of the barrel acting like a brush that it was going to sweep the target out of the sky.

Close Range Shooting

For close range shooting, the trigger is pulled just as the muzzle passes the bird’s head. For longer shoots, the trigger pull comes after the muzzle has passed the bird by a distance that is one, two, or three times the length of the bird’s body. Sometimes, fast flying ducks and geese at distances of fifty or sixty yards are killed with leads the length of a car.

One time, after my buddy Ronny Boehme dropped a high-flying Canada goose, he jokingly estimated his lead as “about a Greyhound bus.” Unfortunately, there is no formula or rule that can help you calculate lead distances. These are decisions that are made instinctively, in the heat of the moment. Again, the key to successful wingshooting is practice, practice, practice.

Conversation