How One 80-Year-Old Angler Might Change Colorado Stream Access Forever

On a bluebird day in August 2012, a 71-year-old fly fisherman named Roger Hill was wading his favorite stretch of the Arkansas River, just downstream from Salida, Colorado, when he noticed a baseball-sized rock falling from a high bluff above his head.

The rock plummeting toward him—the first of several to come—had been pitched off the 50-foot bluff by an adjacent landowner named Linda Joseph. Her rationale for hurling large stones in Hill’s direction was simple: She believed she owned the riverbed that Hill was standing on and that, in fishing there, he was trespassing on her private property.

A retired physicist, Hill knew exactly how much velocity the rocks were gaining as they continued to rain down, and being on the mend from a recent heart surgery, he had legitimate fears for his life.

“By the time a rock has fallen 50 feet it’s traveling at a speed of 40 miles per hour,” Hill said, in an interview with MeatEater. “I was on blood thinners at the time. If one of those rocks had hit me in the head, I would've had a brain bleed on the spot that could have killed me within the hour.”

Thankfully, Hill managed to evade the falling rocks, and although brown trout were rising to his parachute Adams, he surrendered the disputed stretch of river to the increasingly irate Joseph. He walked out on the same piece of BLM land he’d used to access the river and left for the day.

One year later, a friend of Hill’s was fishing the same stretch of water when Linda Joseph’s husband, a man named Mark Warsewa, fired a .38 Special in his direction. Startled but otherwise unharmed, the fisherman later pressed charges, and Warsewa, who claimed he was only firing a warning shot, was sentenced to 30 days in jail for the crime of “menacing.”

“He had a double-handed grip on the thing,” Hill said, recounting his friend’s story about the encounter with Warsewa. “He squeezed off one shot that missed the guy by about 10 feet and skimmed off the water. He was going to fire another, but the gun jammed.”

These hostile encounters with Linda Joseph and Mark Warsewa have kept Roger Hill, now 80 years old, from fishing his favorite stretch of the Arkansas River to this day. But some 10 years after the first incident, he is finally reaching the culmination of a court case that could permit him to return.

Hill’s case is known asHill vs. Warsewa, and it may be one of the most important public access cases in the country today. Put simply, the plaintiff argues that anglers have a constitutional right to wade in and fish the stretch of the Arkansas River that borders the Warsewa property. In denying him access through a variety of threatening means, Warsewa and Joseph are in violation of those rights, Hill claims.

In the four years since he filed the case, it has cleared a series of daunting legal hurdles. Despite steady opposition from Warsewa’s legal team and the State of Colorado itself, the case is now awaiting trial in a state district court in Fremont County, Colorado.

If the state district court decides to hear the case and ultimately rules in Hill’s favor, the decision could clear the way for a significant liberalization of Colorado’s stream access regulations, affording anglers access to prime waters all over the state—some of which have been locked up for a century or more.

Questioning theStatus QuoLong before his run-ins with Joseph and Warsewa, Hill knew that his right to fish the Arkansas River could be called into question. After all, Colorado had—and still has—some of themost restrictive stream access laws in the country.

Hill, who is highly educated in the intricacies of stream access law, has fished in Colorado for more than 50 years. In 1992, he authored aguidebookon fly fishing the South Platte River. During his time exploring the state’s network of rivers, he’s seen the landscape change dramatically.

“When I first came to Colorado in 1967, I could go to the Arkansas River and I could fish damn near anywhere,” he said. “Over the years, fences started going up, the posted signs started going up, and the places I can go fishing are severely limited at this point.”

While he lamented the loss of fishing access in his home state, Hill says he found respite in a nearby state to the north.

“I fished Montana regularly,” he said. “In Montana, if you want to fish in a stream, if you can get in it without trespassing, have at it—no further qualifications required.”

After fishing the famous rivers of the Big Sky State for a number of years, Hill became enamored with the state’s liberal stream access law. He relished the opportunity to wade any river he wanted, so long as he entered at a public easement or bridge and remained below the stream’s high water mark. Eventually, he began to wonder what it was about Colorado’s laws that prevented a similar culture of public access from flourishing in the Centennial State.

“I started asking knowledgeable people in Montana about that and they said, ‘Roger, it all has to do with navigability,’” Hill said.

Navigability and Public AccessUnder federal law, the ground beneath a body of water belongs to the state if that waterway was “navigable” at the time of statehood. This rule is codified in the U.S. Constitution via a legal principle known as the “Equal Footing Doctrine.”

The Equal Footing Doctrine harkens back to a period of American history when states were being added to the Union one by one in piecemeal fashion. As new states trickled in, each one had to enter on an “equal footing.” Part of that equality of entry meant that the ground below all “navigable" waterways, from ephemeral streams to sweeping shorelines governed by the tides, must be held in trust by the state for the benefit of its citizenry.

Navigability, as defined by law, depends on the capacity of a given waterway to act as a corridor for commercial activity. If a waterway supported commerce, it is said to be navigable, and is thus owned by the state in perpetuity. There is a strong argument to be made that the Arkansas River—as it flows past Texas Creek where Roger Hill was fishing at the time of the Warsewa incidents—was routinely used for commerce around the time that Colorado was admitted into the Union.

“The way this works is, you have to make a case that the stream section was used or was susceptible to being used in its natural state as a highway for commerce at the time of statehood,” saidMark Squillace, Hill’s attorney in the case and a professor of natural resource law at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Squillace and another attorney named Alexander Hood are representing Hillpro bono.

“We’ve hired an expert and we have what we think is pretty strong evidence of historic uses of the Arkansas River for various kinds of commerce,” Squillace told MeatEater.

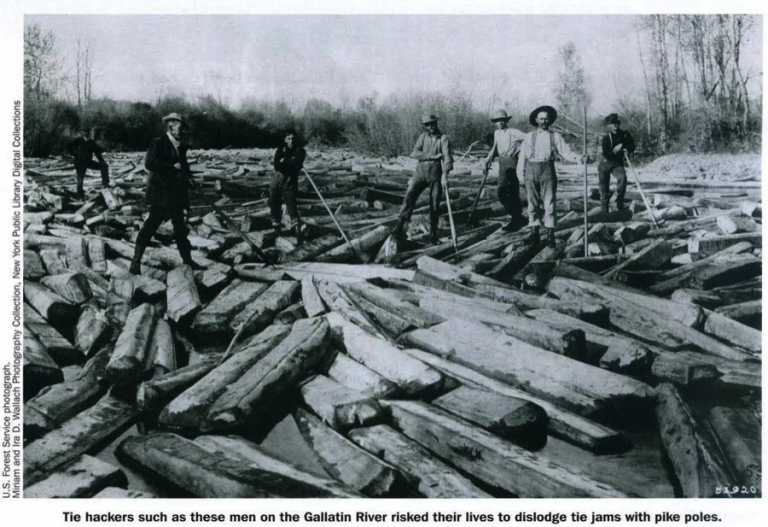

Those commercial uses are well documented. They range from massive “tie drives,” during which loggers would force tens of thousands of freshly-cut wooden railroad ties down the Arkansas, to a lone account of a beaver trapper floating furs past the very spot where Roger Hill would encounter Linda Joseph more than 200 years later.

Tie Drives and TrappersIf Roger Hill is ever allowed to stand in his favorite stretch of the Arkansas River again without being pummeled, he will have a hardy set of 19th century loggers and a mountain man named Ezekiel Williams to thank for the privilege.

Jim Sherow is a historian who’swritten extensivelyabout water resources in the Arkansas River Valley. He’s the expert witness who Mark Squillace has hired to help him prove navigability in Hill’s case.

“In the late 1870s, thousands of logs were cut in the upper portion of the Arkansas Valley, not too far from the town of Leadville, Colorado,” Sherow told MeatEater. “They were floated down the river past Texas Creek, which is called into question in this case. This went on for as long as it took to build the Santa Fe and Rio Grande railroads.”

Sherow says that a typical “tie drive” involved tens of thousands of logs descending the Arkansas during the spring runoff. Before they were sent downriver, the logs were rough-hewn in mills near Leadville—hacked into a form that could be utilized by the burgeoning railroad industry. During periods of heavy spring runoff, the site of a log-choked Arkansas created a stir in nearby communities.

“The newspaper in Pueblo, Colorado, would talk about when the ties were going to come down and pass the city,” Sherow said. “It was quite a spectacular site to see all those ties coming down.”

While they make for strong evidence, tie drives aren’t the only example of commerce along the Arkansas River around the time of Colorado’s statehood.

“The upper Arkansas was heavily hunted out for furs during the beaver trapping era,” Sherow said. “We just don’t have many surviving records of fur trapping in the era, which is why the case of Ezekiel Williams is so unusual.”

Ezekiel Williams was a trapper from Boone’s Lick, Missouri, who worked traplines along the Upper Arkansas with the help of the Arapaho Tribe.

“It was dangerous work what he was doing at the time,” Sherow said. “He had the Blackfeet to contend with as well the Canadian fur companies and the Spaniards, who asserted a lot of control over the Arkansas River back then.”

According to Sherow, Williams wrote an account of his trapping exploits along the Upper Arkansas for a Missouri newspaper. It describes Williams floating a substantial cache of beaver pelts through the same section of river that’s being disputed in the case. The account shows that Williams was headed downstream to bring the furs to market—a clear indication of commercial activity.

Opposition and SupportThough Squillace is optimistic about his legal team’s ability to prove that the Arkansas is indeed navigable, he’s yet to see his day in court. He says that the state, which has maintained for over 100 years that therearenonavigable rivers in Colorado, has fought his client at every turn.

“We have to get this resolved somehow, and Colorado has been very reluctant to have any of this resolved in any way, shape, or form,” Squillace said. “They don’t want to talk about it. We have anattorney generalwho has been fighting us tooth and nail and seems to be beholden to private property or water rights interests.”

Squillacesays that the water rights community opposes Hill’s case on grounds that are baffling and unsubstantiated.

“For some weird reason, the water rights community is just adamantly opposed to this case to the point that they think we’re trying to steal their water rights,” he said. “We’ve tried to tell people that this case has nothing to do with water rights. We’re not claiming a right to any particular amount of water in the stream. We’re just claiming that, if there is water in the stream, and it’s fishable, people have a right to stand on the bed of the stream if it is navigable.”

More obvious to Squillace is the motivation of the large landowners in Colorado who are also working to oppose his case.

“The other big group that’s opposing us is the landowner community,” he said. “Here in Colorado there are a lot of very wealthy landowners who basically cut out the public on what they consider to be their private streams.”

According to Squillace, many of these “private” rivers and creeks could ultimately be deemed navigable for title if reviewed by a court of law, thus opening them up to the potential for broader public access.

“[The landowners] don’t want any court claiming that there could be navigable rivers and streams in Colorado,” he said. “They issue permits and licenses to people for a hefty sum of money to fish these streams.”

In his quest to open public access to Colorado’s rivers, Squillace says he has enjoyed the steadfast support of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers.

“They have been terrific,” he said. “They’ve reallypublicizedthis issue to their membership and have been supporting us from the very beginning.”

He’s less enthused, though, with the popular fly fishing and coldwater conservation group Trout Unlimited.

“TU refuses to support us in this case,” Squillace said. “A lot of the rich landowners support Trout Unlimited, so they’ve been reluctant to stand up with us.”

Trout Unlimited declined to comment for this story.

Roger Hill believes that the State of Colorado is stalling because it doesn’t want to work through the complicated consequences his case could have for large landowners in the state.

“The state is doing everything it can to keep from having to deal with the problem of explaining to rich ranch owners: ‘No, you didn’t lose anything, you just never owned it, and how can you lose what you never owned?’ They don’t want to do that,” Hill said. “I, and thousands like me,havelost something by not having access to streams we should rightfully be able to fish.”

Getting Back on the WaterRoger Hill has high hopes for the outcome of his case, but he’s growing impatient with the state’s ongoing refusal to grant him a fair trial.

“It’s been a long, bloody struggle,” he said. “I’ve devoted 10 years of my life to this thing. It’s a lot of work, and it’s gone on so long, and I’ve gotten so damn old at this point, that I don’t have the strength to wade the big rivers anymore—I can’t do it.”

He prefers more moderate waters, like those found on the disputed stretch of the Arkansas River that his court case stems from.

“It’s a great spot to fish,” he said. “The river is fairly wide. There are a lot of rocks. It’s not too deep but deep enough to provide good cover for trout. It’s not so fast that you can’t get in and wade around.”

According to Squillace, if he and Hill succeed, the implications for Colorado’s fishing community could be broad, opening up not just the Arkansas but many miles ofde factoprivate streams to public access. But he says that the state shouldn’t do that by litigating the navigability of each river or river segment on a case-by-case basis.

“If we win, and I’m hopeful that we will ultimately prevail in this case, the goal is to convince in the governor at that point that it’s time to appoint acommissionto sort through the various rivers in Colorado and determine which of those meet the navigability for title test,” Squillace said. “I think it would be highly problematic to have to litigate every river system, indeed every river segment in the state.”

Hill says that, if that day ever arrives, he’s heading back to Arkansas where it flows past Texas Creek. It’s as good a fishing hole as he’s found anywhere in the state.

Shop

Sign In or Create a Free Account

Related

Public Lands & Waters

How One 80-Year-Old Angler Might Change Colorado Stream Access Forever

Public Lands & Waters

New Mexico Supreme Court Restores Public Stream Access Law