The Rise and Fall (And Rise Again) of the American Small Game Hunter

It’s no secret the MeatEater crew lovessmall game huntingas much as chasing big bucks or spring gobblers. We grew up small game hunting with friends and family, and we never gave it up. But despite the rich tradition and history of small game hunting in this country, the majority of current American hunters spend little time, if any at all, hunting small game.Squirrels and rabbitsbarely register as worth the effort. Even upland birds and waterfowl take a distant backseat to the more glamorous pursuit of antlers and spurs. This hasn’t always been the case, and it’s a situation we’d love to see change.

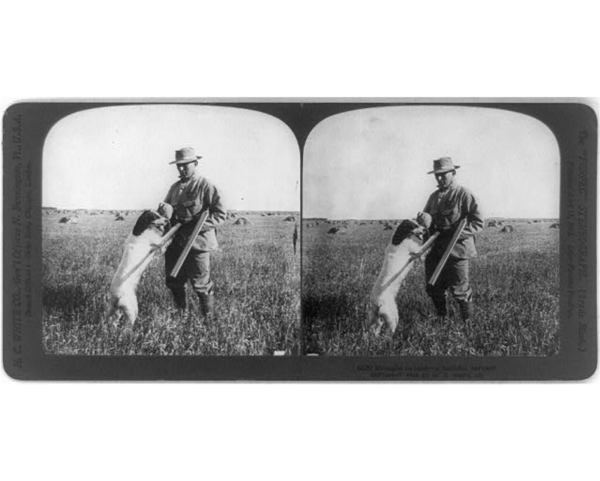

Just after the turn of the century, market hunting had depleted many of America’s most coveted game animals, like bison, whitetail deer, elk, and wild turkeys.Teddy Roosevelt and company reacted swiftly, implementing much needed conservation lawswhich would eventually lead to the recovery of many game populations. In the early decades of the 20th century it was slim pickings for venison and poultry, especially in the eastern half of the United States.

That didn’t stop recreational hunting from booming after World War II ended. As millions of young men returned home with an interest in the outdoors, sport hunting experienced a gigantic surge in participation. With this influx of new American hunters, small game hunting became an extremely popular activity, even among urban citizens. Although deer, turkey, and waterfowl numbers remained low throughout much of the country, there was no shortage of cottontail rabbits, squirrels, ruffed grouse, quail, and wild pheasants. Small game hunting was a genuinely respectable pastime in America, and most hunters enjoyed hunting for everything in a generalist manner rather than specializing in singular trophy pursuits. Popular hunting magazines likeField and Stream, Outdoor Life,andSports Afieldregularly dedicated feature articles and front page illustrations to all manner of small game species. When’s the last time you saw a cottontail rabbit on the cover of a major hunting magazine?

Access for All

Access for these hunters was plentiful. Public land opportunities were readily available in the squirrel-filled hardwood forests of the Northeast. On private lands, permission to hunt was granted readily—if it was even required at all. More often than not, a hunter could simply pull off of any dirt road in Wisconsin or Iowa and start hunting fence rows and brushy fields for pheasants or cottontails on whichever farm looked promising. In places like Maine, logging companies hadn’t yet begun to post their properties and grouse and snowshoe hare hunters could go pretty much anywhere they wanted. In the south, quail and rabbits were plentiful. Finding places to hunt was damn easy and the small game hunting was as good as it gets.

This trend continued for several decades. Hunting participation peaked in 1982 with over 17 million licensed hunters in the U.S., and interest in small game hunting remained strong. Even as deer and turkey populations recovered and interest in those species rose, hunters continued to pursue small game. As a young hunter in the early 1980s, I hunted deer with both archery gear and rifles, but spent the majority of time in the fall hunting whatever small game I could find. Later, when driving became an option, even more small game hunting areas became accessible. It wasn’t uncommon for my buddies and I to come home with a mixed bag consisting of squirrels, rabbits, pheasant, ruffed grouse, woodcock, wood ducks, or mallards.

About that time, things began to change.Hunter participation began to dropsteadily as the country became more urbanized and interest in the outdoors waned.A shift in interest also began for many of the remaining hunters.Killing big whitetail bucks became themajor focus of hunting media, and hunters went all in (and still do to this day). At the same time, traveling west to hunt elk, mule deer, and pronghorn was growing increasingly popular. Booming wild turkey populations were reaching a point where hunters all over the country started to take notice. These phenomena have only become more entrenched in the culture of American hunting in the intervening years. It’s gotten to the point where small game hunting has largely fallen by the wayside—a forgotten relic of a bygone era for many modern hunters.

Loss of Habitat

However, hunting media and big antlers aren’t the only reasons small game hunting participation has dropped. In some cases, habitat loss due to modern farming practices, commercial and residential development, and the lack of thinning overly mature forests have played a significant role as well. In the past, small farms commonly left portions of their property fallow. Woodlots, brushy fields, and wetlands were left untouched. Fence rows and creek bottoms were defined by thick brush. This made for great habitat for small game and upland birds. State-managed forests were regularly thinned and logged, which also provided new growth and thick brush that is attractive to ruffed grouse and rabbits.

Sadly, much of that habitat doesn’t exist anymore. Large-scale agriculture operations practice fence-to-fence farming that offers little year-round habitat for animals. A growing population has spread into the rural countryside replacing small farms, wetlands, and woodlots with big subdivisions. Even where family-operated farms remain, theConservation Reserve Program,which pays farmers to leave portions of their property as natural habitat, is in a constant state of flux depending on the current demand for corn and wheat. In surplus years, farmers are happy to be paid to leave wildlife habitat intact, but when demand for corn and wheat is high, small farms can’t afford not to plow those fallow fields under to grow crops.

Managing forests for the sake of small game and upland bird habitat is an expensive endeavor, and some state governments have trouble funding these projects, especially as hunter participation and hunting’s associated conservation revenue has fallen. In short, it’s gotten harder to find good places to hunt small game.

The Small Game Revival

All is not lost, and there seems to be a vigorously renewed interest in small game hunting across America. While there is less productive small game habitat than there was 40 years ago, there’s also way less hunters pursuing small game. My father’s property borders state game lands in northwestern Pennsylvania. While this piece of public hunting land gets pounded by dozens of hunters during the rifle deer season, virtually no one ever hunts it for squirrels. I can vouch for the fact that there’s a load of fox and gray squirrels there. You’ll find this is the case on public hunting areas throughout the country. In all the years I’ve been chasing mountain cottontails during the winter in Colorado, I’ve never run across another hunter. Even in well-known destination upland bird areas in Nebraska, I’ve usually got hundreds of acres of prime pheasant and bobwhite quail habitat to myself during the week when other hunters are working.

There are plenty of opportunities out there for burgeoning public land small game hunters. Even where state and national forest land is lacking, most states offer wildlife management areas, state game lands, and public access to private land through collaborative arrangements.

When it comes to securing access to hunting private land, many farmers and ranchers are much more willing to give small game hunters permission than those seeking access to hunt deer or turkeys.

As aging baby boomers drop out of hunting with increasing frequency, we need more new hunter participation. Currently, it’s estimated there is just over 11 million licensed hunters in America. Luckily, the interest small game hunting is picking up once more. There is a growing number of individuals who are joining the hunting ranks because they’re interested in sourcing their protein supply from wild game, and small game hunting is an easy entry point. Killing a deer is certainly an effective way to fill up the freezer with wild protein, but stacking up a bunch of small game and upland birds adds a lot of variety to your diet.

There’s no doubt we love spending an entire week searching for that one special buck, bull, or boss gobbler, but it sure as a hell is a lot of fun hanging with a couple buddies and kicking cottontails out of brush piles and scanning oak trees for squirrels. The only thing better is enjoying the meal you make with them after the hunt.

Shop

Sign In or Create a Free Account

Related

Small Game

The Rise and Fall (And Rise Again) of the American Small Game Hunter

Small Game

Tips for Recovering Downed Small Game