Popular searches

Articles

Series

Topics

Shop

Recipes

For a sport so consistently full of inconsistencies, it’s a wonder why steelheaders put so much emphasis on the perfectly sculpted Spey cast. With variety that could rival a box of chocolates, each angler not only fishes differently to one another, but casts with their own flavor as well.

There are the anglers who are more concerned with their cast than their hookup ratio, and the anglers who are hopeful to simply land their fly in the water. Then there are the rare anglers who are talented at both casting and fishing, and the anglers who are happy just to sneak a moment out of the house!

I remember the days when I was insecure about my casting. Perturbed by a collapsed loop or a tailed sink tip, I would mutter profanities, strip in my running line and recast it “properly.”

It wasn’t until I came to appreciate my accumulated experience as an angler – rather than a caster – that I simply stopped caring about the aesthetics of my yellow floating line and began to let even the poorest of casts fish themselves out. Naturally it was no surprise that my catch rate skyrocketed. After all, how is a fly supposed to catch a fish if it’s not in the water?

I am fortunate enough to spend a great deal of time with other anglers. As a guide, it is my job to observe and recognize fishing patterns while spending time with my guests. But the truth is that only fifty percent of my guests are competent Spey casters. Regardless, the poor casters catch just as many fish as the excellent ones. Sometimes they even catch more! It’s baffling.

I can only accredit the success to physics. A collapsed cast often lands in a pile, where it is then given the ability to sink deeper than if it were cast on a taut line. This can be beneficial when steelheading. In the single-hand world we use a cast called a ‘pile cast’, where the line is deliberately crumbled atop the water to allow for a dead-drift. While this may be deemed an error in Spey casting, it’s an error that comes with a pretty awesome reward.

It would irresponsible of me to say that learning how to cast is unimportant. A knowledgable Spey-caster is far more comfortable in highly probable scenarios of pesky wind, heavy flies, overhanging trees, and riverbank obstructions, however, it’s undeniable that even bad casts catch good fish.

Contrarily, often the best casters are eager to wet a long line, so they tromp out to the middle of the river and cast as far as they can. This can result in them either stepping on the fish close to shore, or casting over the lie where the fish are holding. Angled downstream, they often swing their fly too far, too quick and too unfocused to demand any attention from migrating steelhead. These are my favorite people to fish behind. They are beautiful to watch, perfect to learn casting tips from, and are incredibly courteous by leaving plenty of untouched steelhead for those of us who can’t (or don’t) cast as far.

Then there are the anglers who don’t even pretend to know how to do a left-hand-up snakeroll at 150 feet. More concerned with how their fly looks after it is in the water, these are the anglers who have put their time in to understand water hydraulics, fish behavior, and maximum efficiency.

Naturally, there are some who possess all of these great qualities, but this comes with time, experience, dedication and a little natural talent.

It should also be mentioned that there are often conditions that push fish close to shore. Colored water and poor visibility will drive both migrating and holding fish closer to the riverbank. I have witnessed countless occasions where an angler casts no further than fifteen feet, yet has been top-rod of the day.

Granted, there is always a way to take things too far, so while I am certainly not suggesting that anglers dump copious amounts of line into holding pools (resulting in a flossed/snagged fish), I am very much encouraging all anglers to allow a messy cast to fish itself out. The river’s hydraulics and undercurrents change regularly, therefore manipulating the fly differently every time. Perhaps that one bad cast will work perfectly in the current and a fish nearby will find it perfectly suitable to eat.

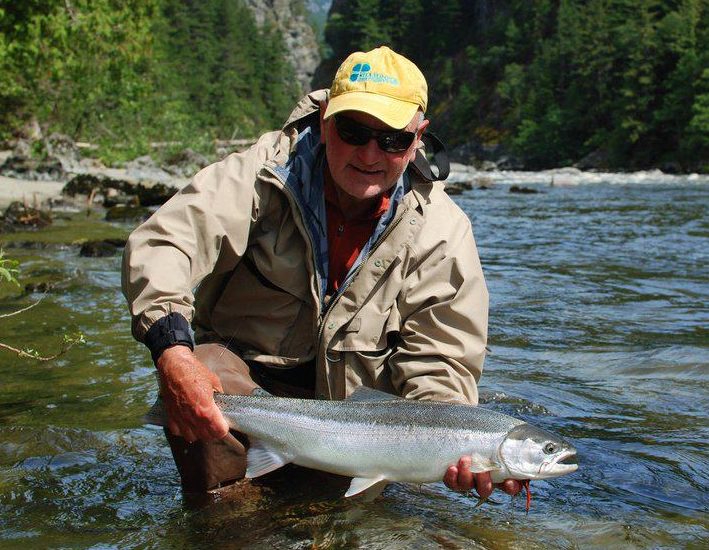

Fish can’t see what goes on above the water, but they sure are interested in what happens beneath it. So before stripping in your next faulty cast, please remember that “even bad casts catch truly awesome fish.”

Conversation