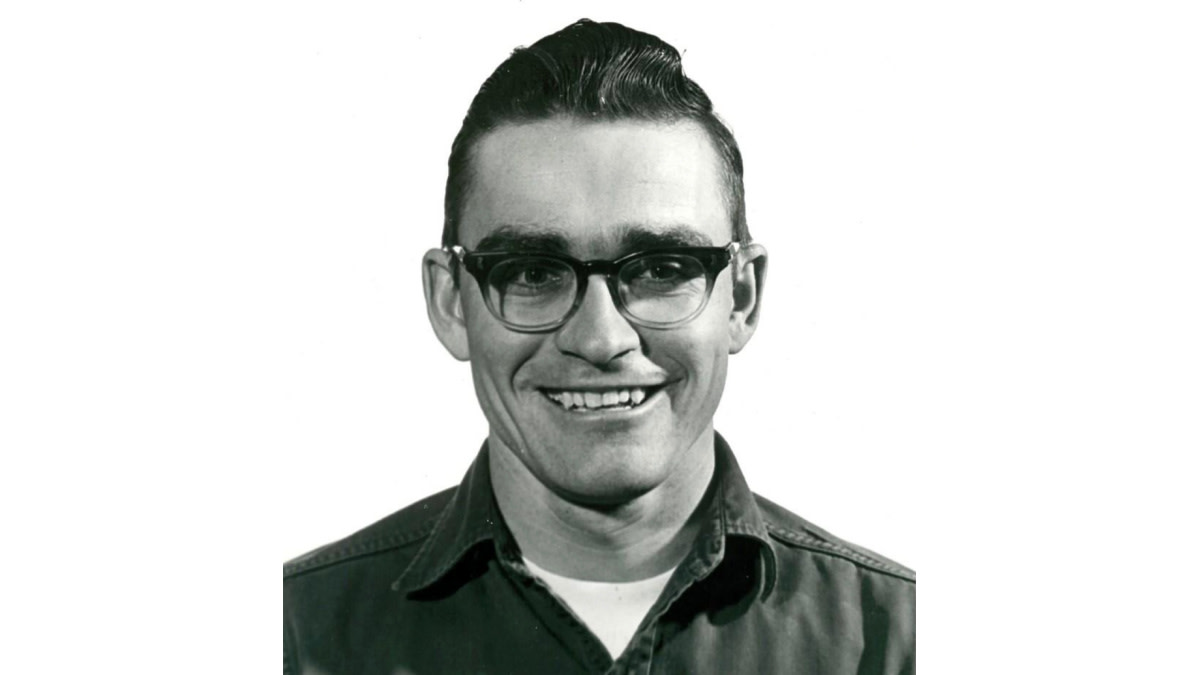

The Savage Murder of Warden Neil LaFave, Part 1

This is Part One of a two-part series on the 1971 murder of Warden Neil LaFave. Part One covers how Brian Hussong decapitated LaFave and the historic investigation for his murder weapon.Part Twocovers Hussong’s daring escape from prison and his 12 weeks spent hiding in the forest.

Brown County District Attorney Donald R. Zuidmulder knew who brutally murdered Neil L. LaFave on Sept. 24, 1971, at the Sensiba Wildlife Area northwest of Green Bay, Wisconsin. He just needed to prove it.

LaFave, 32, a wildlife technician and game warden with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, was shot repeatedly in the face with a .22 rifle. His killer then left the wooded marsh, returned with a shovel and a .30-06 rifle, and decapitated the dead warden. He started the grisly task by blasting LaFave’s neck at least six times with the high-powered rifle and then severing what remained with the shovel blade. He buried the body and head in separate shallow graves several yards north of the murder site.

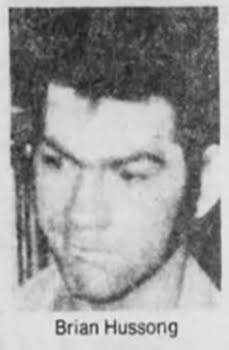

Although Zuidmulder, then 28, knew the murder weapon was a Remington .22, he also knew that rifle wasn’t the key to his case. That distinction belonged to the .30-06, also a Remington. If investigators could find the killer’s deer rifle, Zuidmulder felt sure he could prove Brian Hussong, a 21-year-old, murdered LaFave on the warden’s 32ndbirthday. Hussong was of European descent and described as a “weird, skinny, gangly guy” by another conservation officer.

Hussong, a notorious poacher and violator, had a history of confrontations with LaFave, including a citation the previous autumn for shooting a pheasant out of season. In fact, when LaFave didn’t arrive home for his surprise birthday party that evening, his wife immediately suspected he had been harmed by Hussong. The poacher’s often-bizarre behaviors scared those who knew him, and his lawyer later described him as a paranoid schizophrenic.

All those rifle blasts at the murder scene left behind bullets and shell casings investigators believed came from one specific .30-06. Zuidmulder felt confident Hussong owned that rifle and stashed it after the murder. He doubted Hussong had tossed it into a lake, river, or the waters of Green Bay; he expected that Hussong would eventually lead them to it.

Half-Assed .22

Zuidmulder, a lifelong hunter, also doubted they would find Hussong’s .22 rifle. He was certain Hussong dumped that .22 soon after the crime. Therefore, even though investigators recovered many .22 casings from LaFave’s remains and the crime scene, Zuidmulder considered that evidence circumstantial, barring the rifle’s miraculous return.

He was right. The .22 never resurfaced. “What’s a half-assed old .22 to most people?” said Zuidmulder, now 78 and an 8thJudicial District judge in Brown County Circuit Court. “A .22 rifle is nothing; it’s replaceable. But no one parts with a .30-06. I was sure he hid it somewhere.”

And so it was that Zuidmulder and a relentless team of prosecutors, sheriff’s deputies, conservation wardens, forensics experts, and the state attorney general’s office pursued their case against Hussong. They even made history along the way, securing Wisconsin’s first wiretap warrant, which helped them sweat Hussong into a decisive mistake nearly three months after the savage murder that still haunts Wisconsin a half-century later.

Zuidmulder said it’s impossible to forget the dark night he helped state crime lab agents recover LaFave’s corpse from its shallow grave in Sensiba’s marshy woods. He also can’t forget envisioning LaFave’s wife, Peggy, and their children, Lonny, 4, and Nicole, 2, preparing their home the previous day for a surprise party Neil LaFave never attended.

Law enforcement authorities and volunteers began searching for LaFave the night he disappeared after his wife found his truck at a road’s dead-end inside the wildlife area. LaFave had parked there to post signs along Sensiba’s boundaries.

Some searchers worked through the night, even after officials ended the initial search for LaFave at 1 a.m. on Sept. 25. After reassembling the next day about 6 a.m., they formed a “skirmish line” to continue the sweep.

Sometime that morning a bowhunter named Marvin Olson joined the effort when he showed up to practice with his bow. After spotting fresh dirt resembling a deer scrape deep in the marsh and noticing that a log had been dragged to the site, Olson dug into the sandy soil with his hands. He soon touched a belt buckle and saw an elbow. His shouts summoned investigators, who continued digging with their hands until realizing the body’s head was missing. They immediately secured the site and summoned the state’s crime lab from Madison, Wisconsin, 135 miles to the southwest.

The Search Resumes

When the crime lab’s team arrived that night, Zuidmulder held a large light as they collected evidence while unearthing the body, working slowly toward the severed neck.

“I’m frozen in time there,” Zuidmulder said. “I turned to a deputy and said, ‘You take the lights,’ because I didn’t need to see that. Later in my career I had to go down to a jail where a friend of mine was shot and killed by someone they brought in. Cases like that are as close to combat as you can get. I’m OK, but I learned we need to be more empathetic toward police, firefighters, and other witnesses to traumatic events close to home.”

Investigators resumed searching a small surrounding area for evidence and LaFave’s head. The marshy woods made for slow, difficult work, given its dense brush, standing water, and thick marsh grass.

About 50 feet south of the body’s shallow grave they found the murder site beneath dense brush and vegetation. In a book titled “Protectors of the Outdoors,” former Wisconsin Conservation Warden Jim Chizek said investigators there found LaFave’s pen, sunglasses, notepad, and several .22 shell casings. Nearby they also found a tooth, as well as blood, brain tissue, and bone fragments “spewed in a macabre manner around a concussion area” gouged by bullets fired by a high-powered rifle.

The lead investigators—Conservation Warden Dale Morey and Brown County Sgt. Marvin Gerlikovski—collected evidence as the team cleared all vegetation and gridded a work area covering 300 square feet, which they scanned with metal detectors. Besides bullets and shell casings that the crime lab subsequently determined were fired from .22- and .30-06-caliber Remington rifles, the searchers also found old nails, wire, bolts, oxen shoes and other metallic objects from bygone eras.

On Sept. 28, three days into the search, Brown County Deputy Robert Grant spotted loose soils and forest humus scattered in marsh grass and fallen leaves 60 feet north of the body’s gravesite. Looking closely, he noticed a round plug of earth and a circle of shovel cuts about the size of a bushel basket. He lifted the plug of woodland turf, scooped the sandy dirt beneath, and soon found himself staring at LaFave’s slashed face. The killer had buried the head facing up.

Two Murder Theories

Morey and Zuidmulder have different theories on how LaFave’s murder unfolded. Both concede it’s speculation they’ll never prove because the killer neither confessed nor cooperated.

While searching the murder scene and gathering evidence, Morey found a site where the vegetation looked compressed, as if the killer had waited in ambush. He also found an older digging site near the wildlife area’s boundary where LaFave had posted signs. A botanist who examined lichens in that hole—which was similar in size and depth to the shallow grave holding LaFave’s body—judged it was dug a year earlier.

Morey, now 86, said it’s possible Hussong planned to murder LaFave the previous fall after the warden cited him for poaching the pheasant, but never got the opportunity. Morey said Hussong could have watched from his grandmother’s property nearby for LaFave’s truck and laid a trap the day of the murder.

“He could have gone into the swamp and started shooting with his .22, knowing LaFave was nearby and would investigate if he thought someone was shooting at ducks with a .22,” Morey said. “LaFave got shot while walking a game trail heading that way. Given the setup and what we found, it looked premeditated.”

Morey said he and fellow investigators think Hussong walked to his grandmother’s nearby house after killing LaFave, and returned with a shovel and his .30-06. They noted wide drag marks going north 50 feet from the murder/decapitation site to the body’s grave site deeper in the marsh. They think rigor mortis had set in, causing LaFave’s arms and legs to splay rigidly outward, making a difficult drag through thick brush and rough terrain.

After burying the body, the killer walked north another 60 feet before burying the head. Morey speculates the killer separated the head to hide ballistics evidence from his .22 rifle.

Zuidmulder, however, thinks the killing resulted from a “volcanic rage.” He thinks Hussong erupted when LaFave confronted him deep in the marsh, possibly after hearing his .22 rifle.

“My hypothesis was that LaFave found Hussong with that .22, they had an exchange, and LaFave pulled out his notepad,” Zuidmulder said. “When LaFave started writing a citation, Hussong lost control. There was nothing rational about it. He shot him six, seven, or eight times right in the face with that .22. And then he leaves, returns with a .30-06, blows off the whole back of the man’s head, and shoots his neck to pieces.

“Nothing he did showed evidence of a rational plan to commit a crime and cover it up,” Zuidmulder continued. “All that violence to the body was pointless. It was all anger and rage blowing up. When people get all twisted, you see behaviors that are totally inexplicable.”

Serving Justice

Whether the murder was planned or not, investigators and prosecutors resolved to serve justice. They questioned every hunter who was in or near the marsh that day, as well as every poacher and violator LaFave ever cited.

They also requested lie-detector tests with several possible suspects. Only Hussong declined, on advice of his attorney. Further, Hussong’s alibis for the murder were dubious, including one in which his grandmother claimed he was helping her can tomatoes that day.

Investigators also learned Hussong had a history of mean, angry actions. While fighting with a neighborhood boy when both were grade-schoolers, Hussong savagely bashed the youngster’s head into a cement sidewalk. A neighbor rescued the boy, certain Hussong meant to kill him. And while babysitting a niece, Hussong dismembered her doll while she screamed in terror. Acquaintances also feared him and said he once jerked the head off a kitten that was purring in his lap at a house party.

Meanwhile, investigators used metal detectors to comb sites where Hussong was seen shooting or sighting in his rifles, and dug up an array of spent .22 and .30-06 bullets and shell casings. Ballistics experts couldn’t perfectly match those slugs and casings to similar evidence from the LaFave case, but they appeared the same. Zuidmulder said that wasn’t enough. He didn’t feel confident prosecuting Hussong without the .30-06.

“We had all these pieces to the puzzle, but nothing that fit them all together,” Zuidmulder said. “Everything else was important, but would the jury go for it? As a prosecutor, I wasn’t going to spin the bottle just to see what happens. That deer rifle remained the key.”

Revolutionary Wiretap

In early December 1971, a little over two months after the murder, Zuidmulder contacted Peter Peshek, a law-school friend he’d known since competing against him in high school debates. Zuidmulder and Peshek, an assistant attorney general for Wisconsin, agreed they needed to wiretap Hussong. Telephone taps were new technology and new legal ground, seldom used except in federal cases targeting organized crime figures.

To get a court to OK the maximum three-day wiretap allowed by a newly-enacted state law, they had to show the phone was listed in the suspect’s name or that he regularly used it. They also had to show Hussong would likely use the phone for illegal activity.

Hussong was living at his girlfriend’s place, so investigators hatched a plan to prove he regularly used her phone. They contacted a local flower shop to borrow a delivery vehicle, dressed a sheriff’s deputy as a deliveryman, and sent him to the address with flowers for the young woman. When Hussong answered the door, the “deliveryman” asked for his phone number to verify he had the right address. Hussong obliged, springing the trap.

Armed with the wiretap, investigators now had to get Hussong to make a damning mistake within 72 hours. To apply pressure, Morey followed Hussong everywhere while Zuidmulder executed search warrants. The DA began with Hussong’s aunt, who lived nearby. Zuidmulder also believed Hussong’s grandmother had lied to provide him an alibi the day of the crime, so they prepared a search warrant for her place, too.

“We hoped by following him and searching his relatives’ homes one by one that he’d get nervous and we’d trigger him to call someone about the gun,” Zuidmulder said.

Two days into their plan, Hussong called his grandmother.

“He told her we were up to something, and said ‘that rat Morey’ was sticking his head up everywhere he went,” Morey said. “He told his grandmother not to let anyone have the .30-06 he left with her.”

Zuidmulder executed his search warrant on the grandmother after hearing her tell Hussong: “Don’t worry. That gun is where no one is ever going to find it.”

When investigators showed up, the grandmother claimed she knew nothing about the rifle. After further questioning, she said her daughter had come for it that morning. Investigators escorted the grandmother to their vehicle, drove to the aunt’s business place, and advised her to quit obstructing justice and turn over the rifle.

The aunt produced the Remington .30-06, which was broken down and wrapped in three dirt-soiled plastic packages. Crime-lab tests proved it had fired the shots at LaFave’s murder site. Investigators arrested Hussong on Dec. 15, 1971, at his grandmother’s home after a voice-identification expert verified him on a recorded phone call to his grandmother. It had been less than two months since the murder.

Charged & Convicted

Zuidmulder prosecuted Hussong in April 1972, and the jury convicted him of LaFave’s murder after deliberating for four hours. The presiding judge, Robert Parins, sentenced Hussong to life in prison. As deputies escorted Hussong from the courtroom, he threatened Zuidmulder.

“I stood up as he went by, and he turned around and said, ‘I’ll kill you, you little son of a bitch,’” Zuidmulder said. “I turned around and saw Judge Parins behind me, and wasn’t sure if [Hussong] had just threatened me or the judge. Parins and I joked about that for years, but I’m sure he was threatening me.”

Morey and Gerlikovski escorted Hussong from the courthouse to the Green Bay State Prison. During that drive, he threatened them, too. “He told us if he ever got out of jail he would come after us and kill us,” Morey said. “He told us what happened to LaFave would be like child’s play compared to what he’d do to us.”

To honor LaFave and his public service, authorities placed a large granite monument at the entrance to the Sensiba Wildlife Area in 1972. And, in February 2020, the Brown County Board renamed the nearby Suamico boat ramp as the “Neil LaFave Boat Launch.” His name is also engraved on the Wisconsin Law Enforcement Memorial on the Capitol grounds in Madison.

Click here to readThe Savage Murder of Warden Neil LaFave, Part Two.

Sign In or Create a Free Account

Related

Wildlife Management

The Savage Murder of Warden Neil LaFave, Part 2

Wildlife Management

The Savage Murder of Warden Neil LaFave, Part 1