Scott Farver doesn’t have anything against cats.

When he found a box of abandoned kittens on his north Texas property a few years ago, he nursed them back to health and took them to a local no-kill shelter. But he also understands the dangers that adult free-roaming cats pose to native wildlife. That’s why, prior to 2007, when the Texas Legislature made the practice illegal, his rural community shot feral cats like any other invasive species.

“I thought having cats around would be good to keep the mice down,” Farver told MeatEater. “But we saw that the cats would kill the rabbits, and we could see the impact on the wildlife. Since we haven’t seen any cats in a while, we’ve seen a lot more rabbits.”

Farver’s story illustrates both sides of the feral cat controversy: housecats (Felis catus) are at once a lovable pet and a predatory, invasive pest.

The stalemate should sound familiar to conservationists. Both sides of the debate claim to have science on their side, and it remains unclear which government agency is responsible for fixing the problem. Meanwhile, the divisions grow larger and the threat remains.

The Problem

This debate was reignited last year by a bombshell report published in Science. Researchers estimated that North America has seen the cumulative loss of three billion birds since 1970—a 30% reduction in the total avian population.

“I think it’s reasonable to conclude that cat predation is a contributing factor, especially as it is the top source of direct, human-caused bird mortality in the U.S. and Canada,” Grant Sizemore told MeatEater.

Sizemore is the director of invasive species programs at the American Bird Conservancy. He views the free-roaming cat issue as one of the most serious conservation crises in North America.

An estimated 60 million unowned cats roam the United States, along with another 60 to 88 million owned cats. A 2013 study determined that free-ranging cats account for 1.3 to 4 billion bird deaths and 6.3 to 22.3 billion mammal deaths every year. Since the year 1500, free-roaming cats have contributed to the extinction of 63 species worldwide, according to a separate 2016 study.

Today, cats threaten endangered species like the Piping plover, Roseate tern, Hawaiian crow, Florida scrub jay, Choctawhatchee beach mouse, Lower Keys rabbit, and Key Largo cotton mouse.

“Domestic cats are an invasive species just like any other invasive—Burmese pythons or feral pigs or kudzu,” Sizemore said. “They disrupt the ecosystem in which they’re introduced. They do so through a variety of mechanisms, only one of which is direct predation of wildlife.”

But Peter Wolf, research and policy analyst at the Best Friends Animal Society, believes that the true threat cats pose to native wildlife has been “badly exaggerated.”

“Other than on small oceanic islands, there’s very little evidence, if any, that free-roaming cats have population-level impacts,” Wolf told MeatEater.

Wolf argues that, given the wide variety of threats to birds and small mammals, it’s impossible to prove that cats are responsible for population losses of any particular species. While native animals on oceanic islands are susceptible to invasive predators, the situation in the continental U.S. is much more complex.

Sizemore of the American Bird Conservancy admits that teasing out a single factor is difficult. Still, he finds ample evidence that free-roaming cats have a negative effect on native populations, as anyone whose cat has brought home a dead mouse can attest.

Others argue that cats should be aggressively controlled regardless of their population-level effects.

“It doesn’t matter whether the population is going extinct. It’s the fact that we’re losing the environmental services of those animals,” Stephen M. Vantassel, owner of Wildlife Control Consultant, told MeatEater.

Birds, for example, control insect populations, help with pollination, transport seeds, and are enjoyed by legions of birdwatchers and hunters nationwide. Since cats are an invasive, Vantassel argues that we should not be protecting them at the expensive of native animals and ecosystems.

Threats to Hunters and Game Species

Sizemore is careful to point out that there hasn’t been much research on the threat that cats pose to game species. The largest concentrations of free-roaming cats are found in urban and suburban environments, which reduces their potential impact on game animals.

But Kelly Simon, urban wildlife biologist at Texas Parks and Wildlife, told MeatEater that she’s found domestic cat tracks in some “very remote areas,” and she cited a study from 1974 which found that about one-third of feral cats live on rural landscapes.

These cats can prey on game species, and both Sizemore and Simon mentioned the threat to bobwhite quail, whose populations have declined precipitously since the 1960s.

A 2004 study found that California quail were not observed in locations set up to be “cat areas” for research. Quail were seen or heard “almost daily” in the “no-cat areas,” while they were “never seen or heard in the cat areas,” according to the study’s authors.

Another 2016 study reported that a wildlife hospital in Virginia admitted ruffed grouse, wild turkey, American woodcock, mourning dove, eastern fox squirrel, eastern gray squirrel, and eastern cottontail rabbit with cat-inflicted injuries between 2000 and 2010. Cat interaction was the second-leading cause of small mammal admission and the second-leading cause of bird mortality (abandon or orphaned young accounted for the most admissions of both mammals and birds).

Eastern cottontail rabbits, for example, accounted for the highest number of admissions over the course of the 10 years (4,134), and cat interactions were responsible for 26% of those admissions (1,079).

A similar 2017 study of 82 wildlife rescue centers found that between 2011 and 2015, three of the top four victims of cat attacks were game animals: 1) eastern cottontail, 2) American robin (non-game), 3) eastern grey squirrel, 4) mourning dove.

Killing Whitetails?

Hunters should also be aware of a cat-specific parasite known as Toxoplasma gondii, Sizemore said. It reproduces only in felines, including domestic cats, bobcats, lynx, mountain lions, and jaguars. It is excreted in fecal matter and native animals like whitetail deer can become infected when they ingest contaminated vegetation or water.

“From an ecological standpoint, we’re seeing the results of widespread, free-ranging cats on the landscape being illustrated by large numbers of wildlife testing positive for this parasite. In some cases, it actually kills the wildlife,” Sizemore said.

A 2020 study found that 36% of whitetail deer nationwide were infected with the parasite. In suburban areas, that number jumps to 49.5% and in urban areas it can reach 66.1%, according to a separate 2019 report.

Toxoplasmosis is the second-leading cause of death by foodborne illnesses in the U.S. Humans can become infected by eating undercooked, infected meat. The parasite does not always cause severe symptoms, but it can cause fever or infect any organ. It also presents a real danger to unborn children, which is why pregnant women are advised to not change a cat’s litter box.

Wolf isn’t convinced that the parasite poses a real threat to humans.

“The risks associated with the T. gondii parasite are often overstated—it seems to have overtaken rabies in recent years as the go-to bogeyman,” he said.

He pointed out that the parasite’s life cycle can be perpetuated not only by domestic cats but by bobcats and mountain lions as well, which makes it difficult to quantify the role that free-roaming cats play in the equation. In addition, a 2014 study found that between 1988 and 2010 the rate of infection among people aged 12 to 49 years has actually dropped from 14.1% to 6.6%.

The Solution

If the domestic cat problem is difficult to untangle, the solution is like a Rubik’s cube from hell. While folks like Wolf question the threat that cats pose to animals and wildlife, they still advocate programs that reduce the population of unowned cats in the U.S.

The most popular of these methods is known as Trap-Neuter-Return, which is exactly what it sounds like. Volunteers working with organizations like Best Friends Animal Society and Alley Cat Allies trap free-roaming, unowned cats, neuter or spay them, vaccinate them, and return them to where they were found. Often these cats are living in “cat colonies,” which are cared for by volunteers and community residents.

It’s unclear whether these programs can really knock back cat populations. Two notable studies from Florida and North Carolina demonstrated a decrease in local feral cat populations by 66% and 36%, respectively. But those results may be outliers. Sizemore argues that while some cat colonies may be reduced or stabilized, cats breed too quickly to make Trap-Neuter-Return an effective strategy on a broader scale.

“At a population management level, TNR is neither effective nor humane,” Sizemore said. “The ‘colony attrition’ that occurs is the result of cats being run over by cars, ingesting poisons, being attacked by dogs or coyotes, etc. Furthermore, even if TNR reduced cat populations—which the science shows it doesn’t—these cats would continue to kill wildlife, spread infectious pathogens, and cause a nuisance for surrounding communities.”

The alternative is a combination of education to encourage cat owners to keep their pets away from wildlife and eradication efforts that utilize both euthanasia and rehoming.

“For strays and feral cats, we just need to remove them. Trap, remove, and then do whatever the outcome is that’s feasible in your location. That may be euthanasia, it may be placement in a cat sanctuary, it may be adoption. But under no circumstances should they be left back outside,” Sizemore said.

But Wolf and other TNR advocates argue that while TNR may not be perfect, it is the only feasible solution given the current social and political environment (read: people don’t like killing cats).

“How would we scale up impoundment/killing to a level that would make a difference when the current, relatively modest level is considered unacceptable by so much of the public?” Wolf asked. “TNR is generally the only truly feasible option available, no matter the challenges.”

Who’s in Charge Here?

Unfortunately, the relative costs and benefits of either approach may not matter. As with many conservation issues, it’s unclear who is responsible for fixing the problem.

“Wildlife are getting absolutely massacred by these cats, but wildlife agencies typically do not have jurisdiction over cat management,” Sizemore said. “It’s unclear who, if anyone, has responsibility for the unowned cats.”

Representatives from Texas Parks and Wildlife and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission told MeatEater that their agencies do not regulate domestic cats, and they do not endorse TNR programs. Wolf could not name a single state agency that implements TNR.

Local municipalities can prohibit feeding unowned animals or abandoning pets, but it takes political capital to spend the time and money required to implement either of the two strategies on a large scale.

“If you’re a city councilman, you have to worry about the police force, school districts, etc. Do you really think the cats are going to be high on your list if the cat lobby will light up your phone lines with people screaming about ‘why are you persecuting my cat?’” Vantassel asked.

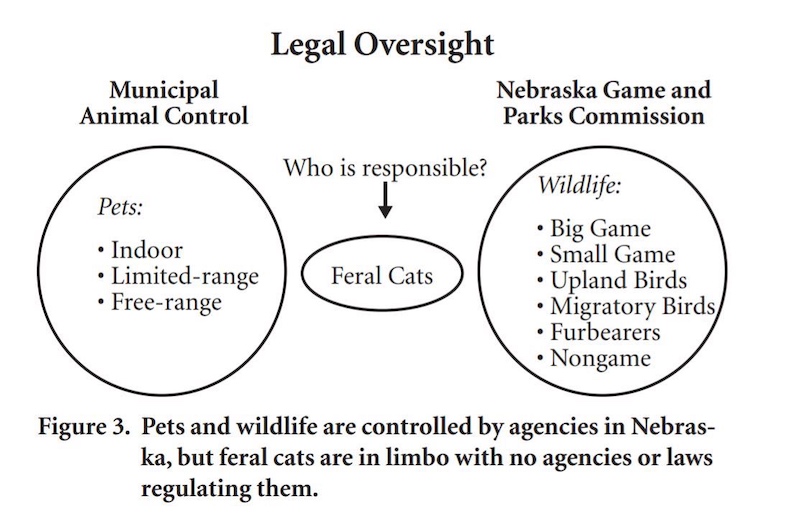

Vantassel co-wrote a report for the University of Nebraska that illustrates the no-man’s land in which feral cats often fall:

As with most conservation issues, politicians are unlikely to act without a push from their constituents. And because this issue is localized, sportsmen and conservationists should start by investigating the feral and free-roaming cat issue in their communities.

Cat owners may be best positioned to make a dent in the problem. Sizemore encourages owners to microchip, vaccinate, sterilize, and most importantly, keep cats away from wildlife.

“I think it’s important to understand that there is a common goal here: the various stakeholders—animal welfare advocates, conservationists, public health officials, etc.—all want to see fewer free-roaming cats,” Wolf said. “This point is often lost in the debate.”

Ultimately, winning the war on (and over) feral cats will take cooperation.