New Findings Challenge Hunter-Gatherer Gender Roles

Take a moment and imagine the world 9,000 years ago—escape the chaos of modern life and enter an untamed, archaic time. Now, travel to the arid Andes Mountains of Peru. You see a group of hunters stalking vicuña. They move together, communicate without a sound, their every step an analytical countermove to the hunted.

Once in range, one hunter stands tall, draws back their atlatl and hurls the spear point with determined strength and accuracy. As the animal falls, the hunter approaches and reaches into the leather tool kit at their side for a sharpened stone point to end the vicuña’s suffering and begin processing the harvest.

Did you imagine the hunter that made the kill as male or female? Western ideals of human evolution rely heavily on the concept of “man as hunter.” However, new findings show that “woman as hunter” may have occurred more than history books ever led you to believe.

Randy Haas and his colleagues from UC Davis recently released the study“Female hunters of the early Americas.”Haas spoke with MeatEater on the recent discoveries.

High-Altitude Forager Societies

“My research examines how forager (a.k.a. hunter-gatherer) societies solve adaptive challenges,” Haas told MeatEater. “As one of the world’s most challenging environments for human survival, the high Andes of Peru is an ideal place for investigating adaptive strategies. So, I was really excited when my colleague Mr. Albino Pilco showed me the site of Wilamaya Patjxa.”

The Wilamaya Patjxa site is located at 12,877 feet in the Andes Mountains in southern Peru. Excavations revealed over 20,000 artifacts and five human burial pits holding six individuals.

“I immediately recognized from the surface artifacts that it was an early site—on the order of 10,000 years old—that could tell us how the first peoples of the Andean highlands solved the challenges of living in a cold, low oxygen, tree-sparse landscape…and did so without all of the fancy outdoor gear we use in the mountains today,” Haas said.

Of the five burials on the site, two were buried with Early Holocene projectile points—tools for bringing down big game. Of the two burials associated with projectile points, one immediately stood out: Wilamaya Patjxa individual 6 (WMP6).

Who Was WMP6?

“We originally estimated that the WMP6 individual was an adult male. We based this on the assumptions that big game hunting was a male activity and the tools that accompany people to the grave tend to be those they used in life,” Haas explained.

“The second assumption is intuitive and demonstrated by previous cross-cultural research. The first assumption is based on observations among recent forager populations, where big game hunting seems to be a male activity. At some level, our own Western understanding of hunting as a gendered activity certainly influenced our interpretation.”

Based on osteological and dental enamel protein methods, researchers determined that WMP6 was actually a 17- to 19-year-old female.

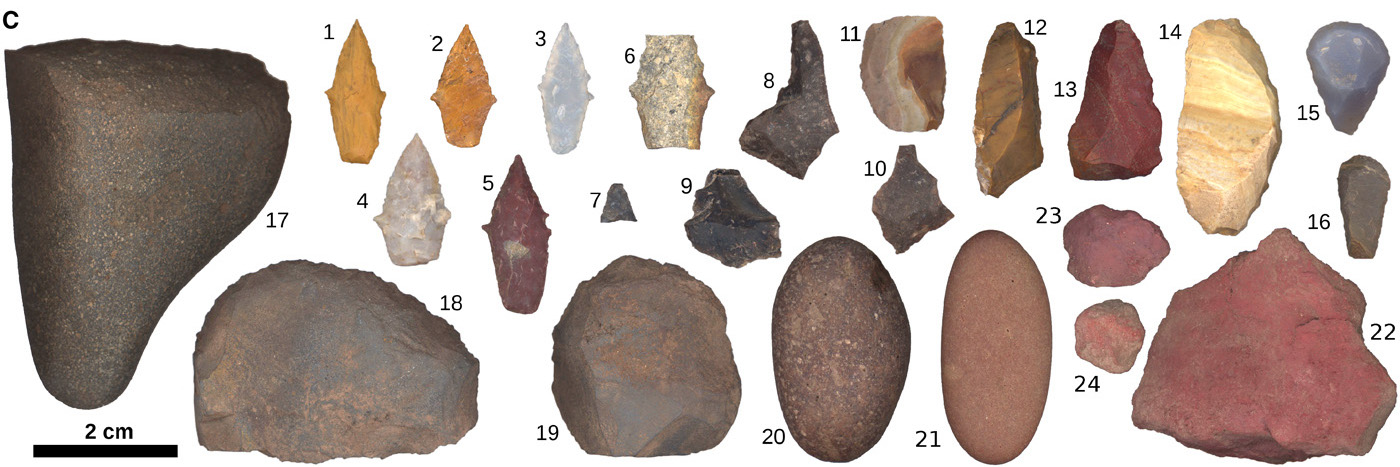

Twenty artifacts were found buried with WMP6, a surprising amount considering the invaluable nature of stone tools for foragers at the time. These hunting tools were stacked on a large stone that had a unidirectional working edge. The stacking of tools indicates that they were placed in a kit, likely a leather bag.

This toolkit includes everything to be a successful Early Holocene hunter:

- Stone projectile points to dispatch big game

- Backed knife and flakes to field dress harvested game

- Scrapers and choppers to extract bone marrow and process hides

- Small scrapers for detailed hide work

- Cobblestones and red ocher used to tan hides

WMP6 was also found with a few bone fragments of large, terrestrial mammals. One vertebra in the burial site was identified as Andean deer, and other mammal bones around the archeological site were found to belong to vicuña, a close relative of the llama, and the deer-like taruca. There were neither small-bodied mammal nor fish elements found at the site, implying that these foragers’ main source of protein was big game animals.

Isolated Incident?

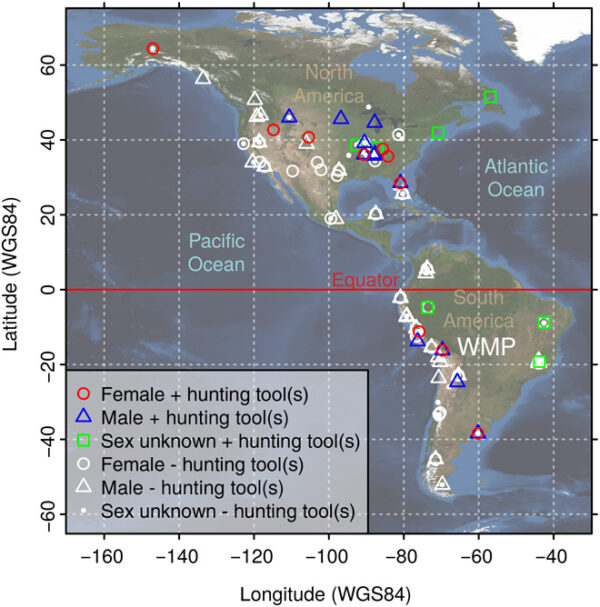

After discovering the sex of WMP6, researchers wanted to know if this was simply an isolated incident or if females hunting big game was a more likely occurrence for this time period. After reviewing Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene burials in the Americas, 27 individuals were successfully sexed from 18 different sites associated with big game hunting tools. Including WMP6, 11 individuals were identified as female, and 16 were identified as male. This somewhat limited data has allowed researchers to estimate that females counted for anywhere from 30 to 50% of ancient American big game hunters.

Women wielding weapons also transcends this Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene time period. A 1,000-year-old Viking warrior burial was unearthed and believed to be male for over 100 years, but has recently beendetermined femalethrough DNA evidence. Additionally, skeletal evidence from Mongolia (1,500 years old) suggests females sustained injuries fighting in battles, likely on horseback with bow and arrow.

Alloparenting and Communal Hunts

Humans are historically meateaters.It’s a defining piece of our evolutionary equation. The hunter-gatherer dynamic is one we have likely been taught in which males hunt and females gather. The concept constructs gender roles long ago in our evolutionary history reliant on the idea that women have one role: reproduction. This makes the assumption that women are then continually tied to children and therefore unsuited for tasks like hunting big game.

There is logic to this, someone has to watch the kids, right? The solution rests in the concept of alloparenting.Alloparenting is definedas care provided by individuals other than parents and is a behavior that has shaped human evolutionary history. Interestingly, alloparenting and communal hunting go hand in hand.

“Communal hunting would have encouraged contributions from females, males, and children whether in driving or dispatching large animals,” the study states. “The primary hunting technology of the time—the atlatl or spear thrower—would have encouraged broad participation in big-game hunting. Pooling labor and sharing meat are necessary to mitigate risks associated with the atlatl’s low accuracy and long reloading times.”

This form of labor organization prioritizes getting meat on the table, and researchers believe these forager communities prospered because of it. Alloparenting caused evolutionary shifts in humans starting with babies because they were forced to “convince” non-kin into liking them. This behavior grew into habitual cooperation with non-kin, which was rewarded by successful communal hunting scenarios. Essentially this behavior grew connections, which built communities—through hunting, shared harvests, and practical childcare.

Future Research

The study has ranked in thetop 100 scientific papers of the yearin terms of public interest. Clearly folks are intrigued by this research, but now more questions demand answers.

“We now know—or think we know—that big-game hunting shifted from being a relatively non-gendered practice to a male dominant activity at some time in the past. So our new question is, why did that shift occur? We are investigating these various possibilities using the archaeological record and areseeking fundsto carry out additional excavations and laboratory analyses,” Haas said.

He has a few working hypotheses on why this change happened. In order to addresswhy, Haas and his team of researchers are attempting to determinewhenthe shift happened.

“Early economies were focused largely on big game because big-game was abundant and human competition was low. So, all able-bodied individuals would have contributed to big game hunting. We suspect that as human populations grew and big-game populations declined, plant foods would have become increasingly important, creating new contexts for division of labor, which may have fallen along sex lines,” Haas said.

Another hypothesis considers the impact of shifting from the atlatl to archery hunting technology around 2,000 years ago. An alternative theory addresses the influence of Western gender ideology and colonial expansion in the last few hundred years.

“To make matters more complicated, it’s also possible that big-game hunting was a female and male activity at all times in the past,” Haas concluded. “But because ethnographers were typically males interested in male hunting behavior, female hunting may have been systematically underestimated.”

Feature image via Matthew Verdolivo, UC Davis.

Shop

Sign In or Create a Free Account

Related

Anthropology

Ancient Hunting Boomerang is Twice as Old as Archaeologists Originally Estimated