A truly one-of-a-kind rifle is about to hit the auction block that represents an important transition in firearms design. This rifle genuinely helped shape and define an era. There are rare firearms—and then there are one-of-a-kind firearms with remarkable stories and undeniable historical significance. The gun in question is certainly the latter.

The ultra-rare Briggs Winchester rifle, set to be auctioned by Kentucky-based Lewis & Grant Auctions this month, is not only the first of an important series of prototype firearms leading up to the creation of the Winchester Model 1866, but it was personally presented by Oliver Winchester to the gun’s designer, George F. Briggs. It stayed in Briggs’ family for almost 100 years.

What exactly is a Briggs Winchester rifle? You’ll need a cool bit of Old West gun history to fully understand that.

“As the former Winchester Museum—now Cody Firearms Museum—curator Tom Hall noted in his letter from 1950, this gun is neither a Henry or a Winchester,” said firearm historian T. Logan Metesh of High Caliber History. “It's one of the experimental ‘missing links’ between the evolution of the two guns.”

Revolutionizing Rifles The Henry Rifle was the first momentously important lever gun introduced in the 1860s. It came at the very beginning of the decade and was a tremendous leap forward for firearms design.

The Henry was produced by the New Haven Arms Company in Connecticut beginning in 1860 and fired the brand-new .44 Henry rimfire metallic cartridge. It could hold an astonishing 15+1 rounds, and the easy-to-operate lever action meant the gun could be fired as quickly as someone could work the action and pull the trigger.

At the time, breech-loading single-shot Sharps rifles that used paper cartridges were considered the pinnacle of rifle technology and had been for many years. Comparatively, the Henry was a wildly futuristic design that could be “loaded on Sunday and fired all week,” as Confederate Col. John Mosby famously said after facing Union troops armed with the repeaters.

What many don’t realize is that the Henry was actually made by Winchester—well, it was made by the company that would become Winchester.

Benjamin Henry worked for Volcanic Repeating Arms, which was founded and operated by Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson (yes, that Smith and Wesson) until it went belly-up in the 1850s. The company’s largest stockholder was a clothing manufacturer named Oliver Winchester. Along with his partner, John M. Davies, Winchester bought the company’s assets and reorganized it as the New Haven Arms company in 1857.

Henry stayed on and continued working on a project he’d started with Smith: a self-contained rimfire cartridge. The result was the .44 Henry rimfire round.

Concurrently, he supervised the design of the Henry 1860 to use his new ammo. Its lever action was loosely based on that of the Volcanic rifle and pistol, which used severely underpowered Rocket Ball ammunition.

The Henry was the first practical repeating rifle and a huge success. But it wasn’t perfect.

The Henry Hop The rifle had two major problems: How the magazine tube worked and how the gun was loaded.

It has tubular magazines with a spring and follower like so many other guns that came after it, but the follower on a Henry is attached to a protruding metal tab, which travels in a long slot cut into the bottom of the mag tube. As rounds are fired and cycled, the tab progresses from the muzzle toward the shooter.

The Henry had no forward handguard—just the barrel and the mag tube protruding from the receiver, which was another problem. So, a shooter would be forced to reposition their support hand to get it out of the way of the moving tab at the appropriate time, or the rifle wouldn’t cycle. This hand movement was infamously known as the Henry Hop.

The tab could also be impeded when the rifle was fired on a rest. Plus, the large open slot in the mag tube needed addressing, because it was an easy way for dirt and sand to get into the works. But why were the tab and slot even there? That brings us to how you load a Henry.

The receiver of a Henry has no opening other than the ejection port on top. When the gun is empty, the tab and follower are near the receiver. At the muzzle, there is a sleeve that goes around the barrel with the front portion of the magazine tube attached to it.

The user pushes the tab toward the muzzle as far as possible, compressing the spring into the front portion of the mag tube, which is attached to the sleeve. The sleeve is then rotated 90 degrees, locking the tab, follower, and spring in place while exposing the open end of the magazine tube where cartridges can be inserted.

Once the gun is loaded, the sleeve is rotated back to its original position, releasing the follower, and the gun is ready to be cycled and fired.

It was a little complicated and damn tough to do on horseback with a 24-inch barreled gun. Plus, the tab would often break off or bend. The mag tube was made of fairly thin steel with a giant slot cut in it and was also pretty susceptible to damage. If it got bent, crushed, or clogged with debris, the rifle wouldn’t cycle.

The First Briggs Prototype Winchester Rifle Things soon went sour between Winchester and Henry. Ben Henry left amidst a flurry of lawyers and suits and Oliver Winchester reorganized the business as the Winchester Repeating Arms Company. He then set about making the necessary improvements to the Henry Rifle.

Winchester put George F. Briggs in charge of updating the gun’s magazine and loading system. Briggs realized all the problems stemmed from the fact that the gun was loaded from the muzzle, so he created a way to load the mag tube from the breech instead. This resolved many of the gun’s issues and made it easier to load from a variety of positions and in the saddle.

The first prototype Briggs created is the very firearm being auctioned by L&G this month.

Amazingly, the gun is in pristine condition, well kept first by the Briggs family and then by private collectors, according to Bill Lewis, COO of L&G Auctions. The firm expects the unique lever gun to fetch between $200,000 and $300,000, but it could go for considerably more. An ornately engraved Briggs Winchester sold for $90,000 in 2013, and another Briggs rifle was sold by Morphy Auctions that same year for $100,500. Neither are as unique as this gun.

“When the gun crosses the auction block in May, some lucky person will be the proud new owner of one of the most important guns in the evolutionary chain between Henry and Winchester,” Metesh said. “Without it, there may well have been no Winchester Repeating Arms Company.”

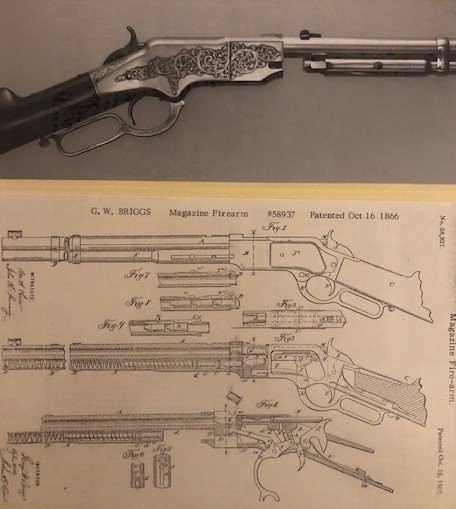

This particular rifle was completed sometime in 1866. The patent for its design was filed on October 16, 1866, and then Winchester purchased it from Briggs.

“This piece in my opinion is one of the most iconic Winchesters you can have,” Lewis said. “I mean, you can theorize: Without this, where would Winchester be?”

How It Works This first Briggs prototype rifle has a lot in common with later pump-action shotgun designs. The muzzle end of the mag tube terminates with a threaded endcap. The length of the tube is solid with no protrusions or openings. Near the receiver, there is a fairly thin, hand-sized metallic sleeve fitted over the mag tube.

To load the gun, one simply pushes the sleeve forward, revealing a loading port on the bottom of the mag tube. Rounds are then individually inserted, much like the loading port on a pump shotgun. The row of cartridges simply compresses the spring one round at a time; no tab necessary. When the tube is full, the sleeve is retracted to cover the port, and the gun is ready to fire.

This rifle’s design is unique even among the very few Briggs prototypes in existence because it has a brass alloy receiver, like the Henry. (The first few hundred Henry rifles had iron receivers.) Later Briggs prototypes used steel receivers, but the Winchester ’66 ultimately had a receiver made from a bronze and brass alloy called gunmetal, which is why the ’66 was nicknamed “Yellow Boy.”

This piece is also the only Briggs rifle that doesn’t have some kind of handguard built over the bare metal slide. Each prototype that followed this first Briggs rifle included incremental changes and improvements over the last. Briggs’ sleeve over the loading port was eventually clad in wood for an easier grip and made into a short forend.

In later examples, the loading port and sleeve concept was abandoned in favor of a loading gate on the side of the receiver covered by a hinged door, which was then replaced by the more familiar spring-loaded door. Moving the loading port to the side also allowed for the addition of a wooden forend to the rifle.

The string of prototypes eventually led to the Winchester Model 1866. It was still chambered for the .44 Henry rimfire cartridge and held 15 rounds, but its new design solved all the aforementioned issues with the Henry Rifle. The rest, as they say, is history.

But that’s not all that makes this prototype special.

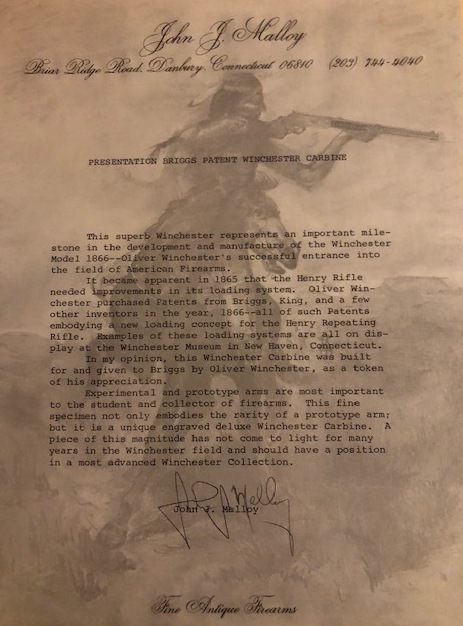

The Provenance Lewis says it’s unknown when Oliver Winchester had the receiver engraved and personally presented to the Briggs family.

“A handful of different experimental rifles were made all around the same time,” Metesh said. “Some of the other guns were also given to people instrumental in helping with the designs—such as one that was given to U.S. Patent Office lawyer William C. Dodge—but this is the only one known to have been given from Winchester to the gun's actual inventor. The fact that it comes with documented family provenance is all the more impressive.”

Among those documents is an interesting letter written by one of George Briggs’ nephews to Winchester in the 1950s asking for information on this strange rifle he found in the family collection.

The rifle is in such immaculate condition because it stayed in the Briggs family for almost a century until it was purchased by Leon C. Jackson, who owned Jackson Arms in Dallas, Texas, in the early 1960s.

John Malloy, a big-time Winchester collector and dealer, later bought the gun from Jackson and sold it through Herb Glass to Richard Mellon. Then, in the early ’70s, Mellon sold a bunch of Winchesters back to Glass. They were, in turn, sold to Malloy, who ended up with the First Briggs Rifle again.

“Then Malloy sold them to the family that is our consigner,” Lewis said. “So the gun has a great provenance and the people who have owned it have been influential people who kept it in great condition. This is as good as it gets.”

Though the gun has never been shot, it likely could cycle and fire. “When you pull the hammer back a little bit and slide the bolt back, you can see both of the rimfire firing pins are still there,” Lewis said. “The extractor heads, which are at 12 and 6 o’clock, are still in place. The bolt is just absolutely mint. The bore is mint. It’s unfired.”

“It really is the granddaddy of Winchester,” he added.