This is part of an ongoing series of MeatEater articles focusing on hunting and fishing for invasive species in the United States. Future articles will highlight individual species and where to find them, specific hunting and fishing methods and recipes for preparing invasives.

A recent study titled Interpreting and Predicting the Spread of Invasive Wild Pigs, published in the Journal of Applied Ecology, predicts America’s wild pig problem is only going to get worse. Current expansion trends suggest that feral pigs are on the move and they could soon establish populations throughout the United States. It seems that the adaptability and fecundity of feral hogs combined with a changing climate is spurring wild pigs to advance beyond their traditional range.

Feral pigs have been present in North America for hundreds of years. Spanish explorers first introduced them to Florida in the 16th century to ensure a local food source. Later, hogs would escape colonial farms to join their feral cousins. Over time, these once domestic animals became firmly established as a non-native but successful wild population. It’s unlikely that anyone at the time foresaw the impact feral pigs would eventually have on our country.

Historically, feral pigs inhabited a small overall portion of the continental United States. Warmer climates and mild topography are ideal habitat for pigs. While common in the Southeast, Texas and coastal California, wild pigs are still something of an alien, exotic animal for many American hunters. Problems associated with wild pigs might seem far off and unimportant to hunters unfamiliar with them.

But, it is now obvious invasive wild pigs, or IWPs, as they are known by wildlife biologists, have created a slew of problems in the United States. Wild hogs degrade and destroy habitat important to native plants and wildlife. Every year, IWPs cost us millions of dollars through agricultural damage, disease prevention, competition with native species, and population control efforts. Annually, wild pigs are responsible for 1.5 billion dollars in agricultural damage according to an article published in Scientific American magazine. In the state of Texas alone, 2.6 million feral hogs are responsible for $500 million dollars in damage costs every year.

Pigs breed quickly and in their current range, there are very few large predators that keep their numbers in check. Primary management tools include live trapping, helicopter gunning, and recreational hunting. The latter has become very popular among hunters who live in pig country. And rightly so, as every hunter should take advantage of any opportunity to kill feral pigs. They’re abundant, great to eat, and can be taken successfully through the use of tracking dogs, ambush hunting, and even spot and stalk tactics in some of the open country of Texas, California and other regions. Bag limits are very liberal (usually non-existent) and seasons are long. But, while chasing hogs is extremely popular, hunting alone is not an effective way to control IWP numbers.

In fact, the demand for wild pig hunts has in some ways exasperated the spread of IWPs. Wild pigs sometimes manage to escape game farms and high fence ranches where wild pigs are actually bred for hunting purposes. Some misguided hunters have even trapped and relocated feral hogs in order to establish new hunting opportunities. These stocking efforts are akin to what’s known in the fisheries world as “bucket biology,” a practice that has had devastating effects on native fisheries throughout the country.

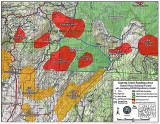

Successful invasive species demonstrate three common traits: establishment of a viable breeding population, rapid movement into new areas, and a competitive advantage over native species. Wild pigs exhibit all of these qualities and present significant issues for wildlife management agencies. Infestations often occur very quickly. Thirty years ago there were no wild pigs roaming freely in Michigan. By 2011, IWPs (likely the offspring of game farm escapees and escaped domestics from small-scale farms) were known to be present in 72 of 83 counties. In order to address this growing problem, Michigan has classified Sus scrofa, Eurasian Wild Boars, as an invasive species. Import and possession of these wild hogs are now illegal in Michigan. In Colorado, there is serious concern invasive feral swine will wander in from Oklahoma and Texas. It is currently illegal in Colorado to possess or import wild pigs and they can be hunted legally without a license all year. Missouri has taken a different approach with regards to hunting. Wild hog hunting is banned on state lands because managers believe that hunting disperses herds of hogs and makes it more difficult for government trappers to eradicate feral pigs. Many other states, including Nebraska, Kansas, Nevada and Utah have outlawed hog hunting altogether.

Managers believe that the best strategy to stem the flow of IWPs is to stop the illegal release of more pigs and to aggressively prevent them from gaining a foothold in new areas where they do turn up. But, despite all state management efforts to limit mounting numbers of feral swine, ballooning pig populations outpace containment efforts. Wild pigs are now utilizing territories that were once inhospitable to them.

The authors of the recent study believe that the average annual increase in temperatures across the United States is likely a contributing factor to exploding IWP numbers. The rate at which pigs are moving northward has effectively doubled, suggesting the previous barrier of colder climates is disappearing. The study’s research model predicts that every county of every state in the lower 48 could host resident wild pigs in the next few decades. As winters become warmer and average mountain snowpack levels decrease, feral pigs may not only advance north but also move towards higher elevations.

Imagine posting up at dawn in your favorite Montana elk meadow, waiting for a bugle, only to see a sounder of wild hogs emerge from the timber. Picture a Maine whitetail hunter, hot on the trail of a buck, surprised to discover he was actually tracking a big feral hog. It might seem far-fetched, but recent research suggests otherwise.

Here in the Colorado Rockies, I hope to never see a wild pig rooting for acorns in a patch of Gambel Oaks but it may only be a matter of time before they arrive. Wild pigs are nothing if not survivors.

Use these links to learn more:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1365-2664.12866/full

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/can-wild-pigs-ravaging-the-u-s-be-stopped/

Brody Henderson is a hunter, fly fishing guide, writer, wilderness production assistant for the MeatEater television show and MeatEater‘s editorial contributor.