Captain Richard Winters was in trouble. Over 100 German troops lay a mere 15 meters from where the American GI stood in the middle of a road, and they had all begun to stand and look in his direction. Fortunately for Winters, he was armed with rifle technology no other major power had deployed en masse during World War II.

As quoted in Stephen E. Ambrose’s book, “Band of Brothers,” Winters explains how he used his M1 Garand to escape a situation that should have been the end of him: “I emptied the first clip and, still standing in the middle of the road, put in a second clip and, still shooting from the hip, emptied that clip into the mass.”

In a matter of seconds, sixteen .30-caliber rounds ate into the tightly packed group of Nazis. Winters leaped into the ditch, inserted another eight-round clip, and began taking more precise shots at the now-running enemy soldiers. The rest of Winters’ company arrived a few moments later, and together they routed the larger force.

Winters’ story is among the more dramatic incidents of the war, but it highlights the incredible advantage the semi-automatic M1 Garand offered American soldiers. Without sacrificing much accuracy, the Garand allowed Americans to pump eight powerful rounds into enemy positions in the time it took their enemy to shoot two rounds using their bolt-action Mausers.

That advantage made the M1 Garand the stuff of legend, and it remains one of America’s most famous rifles.

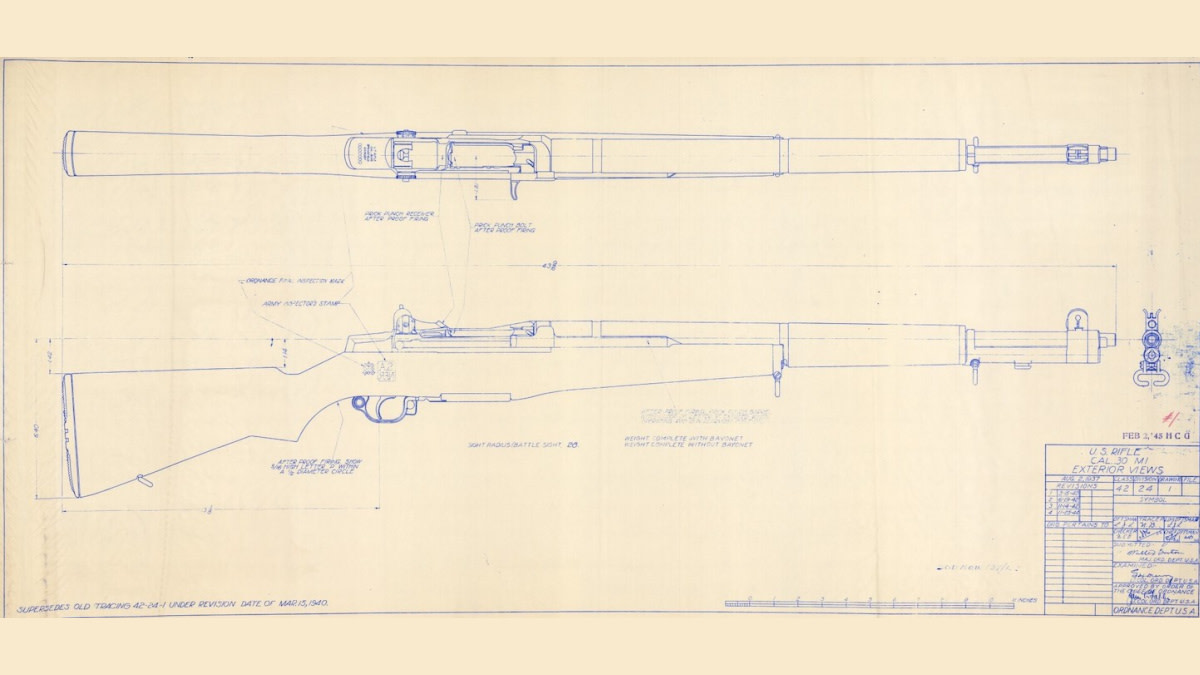

A good example of a standard-issue M1 Garand. (Photo: Cody Firearms Museum)

A Brief History

Semi-automatic rifle technology has been around since at least the late 1800s. Hiram Maxim invented the machine gun in 1888, and even before World War I, many Western powers had begun developing a reliable semi-auto rifle for infantry use.

“They recognized that they’d eventually need a semi-auto rifle to replace bolt actions,” Danny Michael, curator of the Cody Firearms Museum, told MeatEater.

Germany, France, Japan, the Soviet Union, England, the United States, and other nations began semi-auto projects in earnest as soon as World War I ended. Several inventors submitted prototypes to the U.S. Army, but John Cantius Garand’s was the most promising.

After a few failed attempts, he finally opted for a design that was later used by the M1’s successors, such as the M16 and M4. Rather than rely on the detonation of the cartridge to cycle the action, Garand’s rifle siphoned some of the propellant gas to push the bolt to the rear and pick up a new cartridge. This design allowed him to chamber the powerful .30-06 Springfield in a relatively lightweight rifle that could reliably withstand battlefield fire.

The Army adopted the M1 Garand in 1936, which was a relatively uncontroversial move at the time, Michael says. But when the Marine Corps conducted its own testing of several new semi-auto designs in 1940, some started to doubt the Army’s decision.

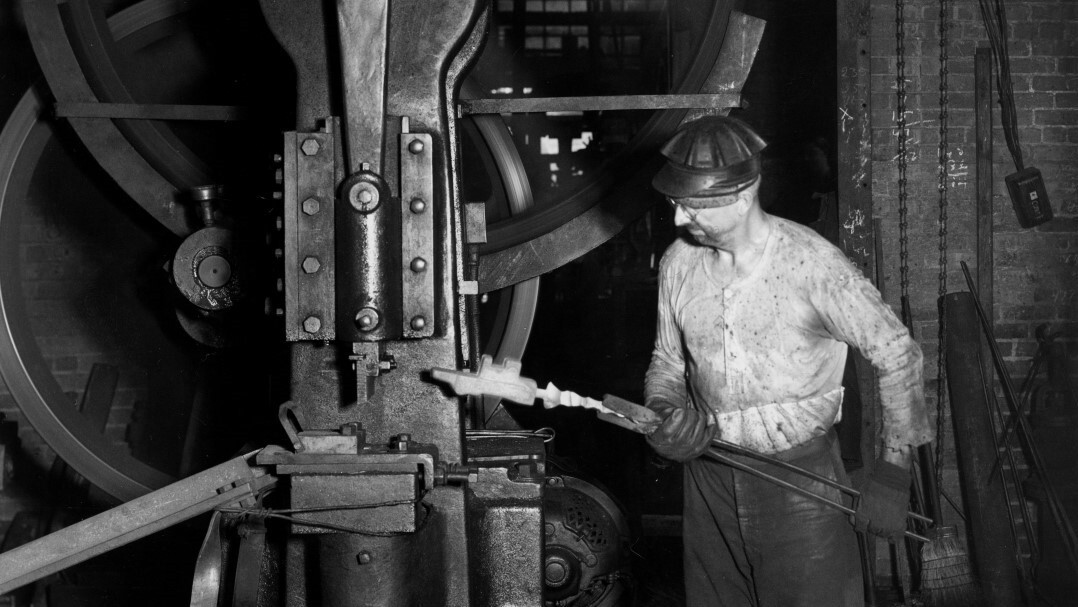

An M1 receiver being forged at a Winchester factory. (Photo: Cody Firearms Museum)

“I think it’s really interesting that this rifle we know as an icon today actually got off to a rocky start,” Michael says. “Any new rifle is going to have some teething issues, but this one rose to the level of a congressional hearing.”

Some, including a competitor to Garand, Melvin Johnson, questioned the M1’s reliability and design. This eventually led to a hearing in the U.S. Congress, but when the Marine Corps tested the Garand against Johnson’s rifle, Winchester’s rifle, and a bolt-action Springfield 1903 (as a control), they adopted the Garand. (For a lengthy rundown of this entire controversy, check out this article in the American Rifleman.)

Garand worked out the rifle’s reliability issues, and the United States was the only major power to issue a semi-auto rifle as the standard for infantry troops. Millions were produced, and by mid-war, every U.S. soldier had access to an M1 Garand. It was so successful on the battlefield that General George Patton famously described the rifle as “the greatest battle implement ever devised.”

Garands were sent to many countries after World War II, so they showed up in other conflicts even after the M16 replaced the M1 in the Vietnam War. The Korean War was the only other major conflict in which the M1 Garand was the standard issue rifle.

Mythbusting

The M1’s history is fascinating, but modern-day myths persist. Chief among them? The “ping!”

As anyone who’s shot a Garand knows, the spent clip makes a loud “ping!” sound when it ejects. According to The Internet, every old-timer at the gun range, and even some WWII veterans, German soldiers would wait to hear the “ping!” before charging an American position. Alternatively, clever Americans would drop empty clips on the ground to lure Germans forward before mowing them down with their semi-auto Garands.

It sounds reasonable in the relative quiet of a gun range, but the theory doesn’t hold much water on a battlefield. While the “ping!” can be heard by the rifleman, it’s unlikely many enemy soldiers were able to hear the sound in the midst of battle. Modern-day tests of this theory have found that even if a German or Japanese soldier could hear the sound, it’s unlikely they’d be able to charge fast enough to capture and kill one soldier–much less a group of them.

Michael says that while the “ping!” trick may have worked in one or two isolated incidents, there were no contemporary accounts of this scenario playing out.

“It all seems to come post-war. To my knowledge, soldiers don’t seem to complain about it during the war, and veterans don’t seem to start talking about it until the gun becomes commonly available after the war,” Michael says. “If it did happen, it’s probably a coincidence. It would be tough to be that opportunistic.”

A rare example of a fully automatic M1 manufactured by Winchester. (Photo: Cody Firearms Museum)

Another common myth about the M1 Garand is that it can’t handle the pressure of modern cartridges and should be shot using only 150-grain M2 ball ammo. While Garand owners should stay away from souped-up cartridges using heavy-for-caliber bullets, Michael points out that the rifle was actually designed for M1 ball ammo, which used a 174-grain bullet.

“The reason everyone thinks you can only shoot M2 ball is because that’s the easy answer,” Michael says. “As long as you’re not hot-rodding a heavy bullet, you can shoot stuff not made specifically for the Garand.”

If anyone is still concerned–or they simply want to limit wear and tear on an 80-year-old rifle–adjustable gas plugs allow users to tune the gun to whatever ammo they’re using. These plugs are easy to install and adjust, and ensure the action receives just enough gas to cycle reliably.

Hunting with an M1 Garand

You won’t have to worry about the “ping!” alerting enemy combatants in the whitetail woods, but hunting with an M1 Garand presents other challenges.

“I think it’s totally usable as a hunting rifle, recognizing that there are limitations as compared to alternatives,” Michael said.

Weight is the first of those limitations. At over 10 pounds loaded with eight cartridges, it’s not the best rifle for high mountain hunts.

“Hunting from a stand, it’s not a concern. But I’ve tried to walk one of these things up a mountain to go elk hunting, and I wished I had my other rifle,” Michael says.

A commemorative chrome-plated M1 Garand for General Patton. (Photo: Cody Firearms Museum)

The iron sights also limit the effective range for most hunters, though this depends largely on how much practice the hunter has with the rifle. The cartridge is capable of taking down an animal out to several hundred yards, and Michael says a good Garand can produce 2 MOA groups.

For most hunters trying for an ethical shot on a deer-sized animal, however, the irons limit shots to within about 200 yards. It’s important to practice and test the rifle prior to heading out into the field, but most Garands can put a round in a 10-inch circle at that distance.

How Can I Get My Own?

If you’ve read this far and you’re a red-blooded American (or just anyone who likes cool mil-surp guns), you’re probably wondering how you can get your hands on one of your own. The bad news is that they aren’t making these beauties anymore. Springfield Armory makes M1A rifles, but if you’re looking for a WWII-era M1 Garand, they’re only getting rarer and more expensive.

The good news is that because the U.S. government made millions of these rifles, they can still be had on the used market. Auction sites like GunBroker and GunsAmerica have many options to choose from, though you’re unlikely to escape for less than $1,000. You can also order an M1 Garand through the Civilian Marksmanship Program at various levels of quality.

Once you have your M1, the serial number can tell you when and where the rifle was made. Michael mentioned that the Cody Firearms Museum has the original serialization records for Winchester-made M1 Garands and carbines, so if someone wants to know the exact date their gun was serialized, they can find that information at the Cody Museum Records Office. Internet search tools like this one can also be good places to start.

Whether your new rifle becomes a favorite range toy or your latest safe queen, it deserves the same level of care the Easy Company gave their rifles.

“When they were issued their rifles, they were told to treat the weapon as they would treat a wife, gently,” Ambrose writes. “It was theirs to have and to hold, to sleep with in the field, to know intimately. They got to where they could take it apart and put it back together blindfolded.”

Editor's Note: This article has been amended to reflect Richard Winters' rank at the time of the action described in the first paragraph.